Practice Template - Eva Illuzzi

Classification

Family: Bacteroidaceae

Genus: Bacteroides

Species: Bacteroides fragilis (B. fragilis)

Introduction

Bacteroides fragilis is a gram-negative, non-spore forming, rod-like anaerobic microbe.[1] It resides in the gut flora of the human microbiota. Bacteroides fragilis remain commensal with the host when in the gut. There, they play an essential role in processing complex molecules into simpler ones in the host intestines. However, if the microbe enters the bloodstream or surrounding tissue it can lead to severe anaerobic infections, most commonly the formation of abscesses.

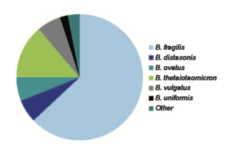

Anaerobes are the most common bacteria in the human colon. Within the group of anaerobes, Bacteroides make up approximately 25% of the anaerobic bacteria within the gut.[2] The Bacteroides genus consists of: B. fragilis, B. distasonis, B. ovatus, B. thetaiotaomicron, B. v ulgatus, B. uniformis, B. eggerthii, B. merdae, B. stercoris,and B. caccae (shown in Figure 2). Of these Bacteroides, B. fragilis is the most frequent isolate and responsible for the majority of the anaerobic infections. B. fragilis is most commonly associated with intra-abdominal infections. A number of these species demonstrate resistance to a wide variety of the current antibiotics.

Pathogenesis and Epidemiology

B. fragilis is often considered the single most important pathogen among the anaerobes that exist in the normal flora. Infections from B. fragilis commonly arise from a break in the mucosal membrane of the intestine.3 The travel of B. fragilis outside of the gut can lead to a variety of infections such as local abscesses at the site of the break, metastatic abscesses by spread through the bloodstream to distant organs, or lung abscesses by inhalation of the bacteria.

Predisposition to B. fragilis can arise from surgery, disease, or trauma.

E. coli, a facultative anaerobe, uses the oxygen at the site which brings the oxygen to a level where anaerobes, such as B. fragilis, can thrive and grow. Due to this phenomenon, many severe anaerobic infections contain a mix of anaerobic and aerobic flora.

Treatment and Prevention

B. fragilis has inherent resistance to penicillin due to its production of β-lactamase. Bacteroides are also exposed to many antibiotics over the course of their lifetime as antibiotics first pass through the digestive tract. This constant exposure combined with its inherent resistance to penicillin leads to Bacteroides being one of the most antibiotic resistant microbes among anaerobic bacteria.

Antibiotics such as clinimycin, metronidazole, carbapenem, beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations (e.g. ampicillin/sulbactam, piperacillin/tazobactam), and cephamycins (cefoxitin, cefotetan, cefmetazole), are some of the only treatments found to eliminate a Bacteroides fragilis infection.5 However, resistance rates to cefoxitin and clindamycin are on the rise.[3] After severe infections, the abcesses commonly need to be drained and the patient should continue treatment with antibiotics. Abcesses in the lungs can usually heal without intravenous treatment.

Preventative measures of B. fragilis infections includes administration of antibiotics prior to abdominal or pelvic surgery.

Bacteroides infection can also be prevented by initial treatment with gentamicin, an antibiotic which targets facultative anaerobes such as E. coli but not Bacteroides.6 Because Bacteroides fragilis infection depends also on the existence of a facultative anaerobe, this antibiotic can be another preventative measure taken to prevent severe anaerobic infections involving B. fragilis. This method, however, does not stop the later development of Bacteroides abscesses. Therefore a more effective treatment combines both gentamicin with clindamycin, an antibiotic that is effective against Bacteroides, prevents the initial infection and later development of abdominal abscesses.

Research

Bacteroides can be used as an alternative fecal indicator organism as they make up a large amount of the normal fecal bacterial flora. Bacteroides have a high degree of host specificity and typically have a low growth potential making them optimal indicators. Due to their sheer numbers, there is a greater likelihood of isolating Bacteroides over other traditional fecal indicators, such as E. coli. As fecal indicator organisms, Bacteroides can be useful for identifying situations of poor sanitation and risk of potential infections from pathogenic microorganisms. The use of Bacteroides as a fecal indicator can determine the potential presence of dangerous bacteria following a flood or sewage contamination in a building as well as identifying fecal contamination in recreational waters. Testing for Bacteroides is often done using PCR analysis.

Conclusion

Overall text length should be at least 1,000 words (before counting references), with at least 2 images. Include at least 5 references under Reference section.

References

- ↑ Wexler HM. Bacteroides: the good, the bad, and the nitty-gritty. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007 Oct;20(4):593-621.

- ↑ Salyers, A. A. 1984. Bacteroides of the human lower intestinal tract. Annu. Rev. Microbial. 38:293-313.

- ↑ Bartlett JG, Fabre V. Bacteroides Fragilis. In: Johns Hopkins ABX Guide. Johns Hopkins University; 2019.

Edited by Eva Illuzzi, student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 116 Information in Living Systems, 2020, Kenyon College.