Murine Gammaherpesvirus 68

Introduction

Murine Gammaherpesvirus 68 (MHV-68) is a rodent pathogen with genetic similarities to human gammaherpesviruses and the Epstein-Barr virus, making it a model pathogen for these human viruses. MHV-68 establishes latency unless the host immune system is compromised, and this latency can be regulated by multiple cellular controls, as virus-specific open reading frames result in gene products that promote the maintenance of latency or activation of lytic cycles. One of the major consequences of MHV-68 in mice is infectious mononucleosis. (1)

MHV-68 is a natural occurring herpesvirus in wild rodents. As a member of the gammaherpesvirus subfamily, it has the ability to establish latent infections within lymphocytes and make close associations with cell tumors. Other viruses in this subfamily include the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (HHV-8) that both infect humans. MHV-68 is similar enough to both EBV and HHV-8 that it can be used as an animal model for study of its pathogenesis. (1)

Other related herpesviruses, including MHV-60, MHV-72, MHV-76, and MHV-78 have also been isolated in bank voles, wood mice, and shrews. Surveys estimate that up to 70% of bank voles and wood mice in the UK carry the virus in the respiratory tract. There is geographical dispersion of the virus, but it was first isolated in Slovakia. These several related viruses caused cytopathic effect, or host cell damage, in epithelium from species other than their natural hosts, including chickens and primates. (2)

Genomic Structure of MHV-68

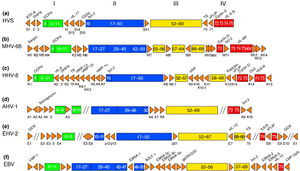

The complete genome of MHV-68 has been sequenced and it has been calculated that at least 75% of its gene products are homologous to HHV-8 and HVS. (1) While multiple viruses within the gammaherpesvirus subfamily have genes arranged co-linearly, there are open reading frames (ORFs) that are virus-specific. (1) ORFs are key in analyzing the gene products of latent and lytic virus cycles, and determining what stimulates the switch from one cycle to the other. Within the gammaherpesvirus subfamily, there is a division between gamma-2 and gamma-1 herpesviruses that is determined by genomic sequencing. The main basis for the genomic distinction within the subfamily is the mechanistic differences in activation from latency to lytic cycles as evidenced by the encoding of gene products. (1)

Open reading frames of significance in MHV-68 include M1, M2, M3, M7, M11, and ORF37 and ORF73. M1 is homologous to the poxvirus serpin protein family, but is not necessary for beginning the latency virus cycle. Its purpose is still unclear, but its gene product may regulate apoptosis or host inflammatory response. (1)

M2 one of the few genes of MHV-68 transcribed during the virus’ lytic cycle. Most genes are transcribed during latency. The M2 locus has been identified as the target for zinc finger antiviral protein (ZAP) binding. ZAP binds to mature M2 mRNA and reduces its expression. Reduced expression of M2 may prevent activation of the lytic cycle, since M2 is overexpressed to induce reactivation. (4)

ORF M3 encodes for a protein that binds to chemokines. (8) Chemokines recruit hemotopoietic cells to infection sites, meaning they modulate immune response in a way that opposes viral infections. The M3 chemokine-binding protein is secreted abundantly to block chemokine function and has been identified as the first binding protein to be involved in chemokine interaction in herpesviruses. (8)

M7 is a virus-specific ORF that encodes for the membrane glycoprotein gp150, which plays a key role in the characteristic of the viral membrane’s attachment and fusion to host cell membrane. (1) M7 is considered a marker of late lytic replication. M11 is a bcl-2 homolog that has been shown to inhibit apoptosis in EBV and HHV-8, and it derived from host genome. The inhibition of apoptosis could function to prolong cell life to allow for an entire lytic replication cycle to occur. (1)

ORF37 encodes viral DNA exonuclease, an enzyme which involved with processing and encapsidation of viral DNA, as well as modulation of host shutoff. Host shutoff is a mechanism highly conserved in gammaherpesviruses and is utilized to provide opportunity for the virus to initiate the lytic replication cycle and infect its host. (7)

ORF73 is reported to be responsible for a gene product critically important for the initiation and continuation of latency, and is unnecessary for lytic replication cycle efficiency. (6)

Genomically, MHV-68 is unique in that at its far 5’ end there are eight tRNA-like sequences, the function of which has yet to be elucidated. The viral tRNAs could potentially be markers for latent infection. (1) Also genomically significant is the ability of gammaherpesviruses to integrate host DNA into the viral genome, as this horizontal transfer allows for continual evolution. In MHV-68 and other gamma-2 herpesviruses there are distinguishable cellular homologous gene products that has been derived from host genome. Gene products from host homologues are predicted to play a role in cell cycle and apoptosis regulation. (1) Genomic manipulation of MHV-68 DNA is useful as a model for study of ORF function by construction of deletion mutants. Gene deletion mutants are also important for investigation of MHV-68 infection mechanisms. (1)

MHV-68 Replication Cycle

Latency replication cycles are common in many viruses, and are a kind of dormancy within the host. The virus maintains infection within the host cells without causing harm, cell lysis, or proliferating its own virions. The viral genome remains in the host cells, yet transcription occurs for select cells, since viral demands differ during lysogenic and lytic cycles. The advantage of latency for viruses is the ability to remain undetected by the host immune system until reactivated into the lytic cycle.

MHV-68 establishes latency in lymphoid tissue, resulting in the enlargement of lymph nodes. (1) MHV-68 latency has an interesting rise and fall pattern in the number of infected cells, as infected splenocytes peak and the decrease as they are detectable within splenic germinal centres. Central to understanding the maintenance of latent infection is the identification of lymphoid tissue cell type that the virus persists within. While vtRNAs serve as a marker of latent infections, it remains to be determined what cell types are targeted. (1)

Infection Mechanisms and Immune Response

Infection sites consist of primarily lung epithelial cells, adrenal glands, and heart tissue, with latent infection in B lymphocytes. (2) Acute lung infection, once resolved, results in lifelong latent infection of lymphoid tissue. Viral targets are primarily B cells for latency rather than T cells. B cells and T cells are both types of lymphocytes, associated with immune response. B cells secrete specific antibodies and are triggered by the presence of a foreign antigen. T cells are responsible for directing immune response and attacking infected cells by recognizing antigens on cell surfaces.

Evidence of this is from the observation that viral tRNA transcription occurs in splenic germinal centres (GCs) during latent infection following acute lung infection, but when inoculated in mice lacking B cells latency is not observed. (1) There is controversy over whether exclusively B cells are targeted, as evidence challenging this claim exists, including the observation that post-acute lung tissue infection there has been persistent viral DNA in an “unidentified cell type”. (1) Additionally, when mice are inoculated intraperitoneally rather than intransally, there has been latency in mice lacking mature B cells noted. Justification for this observation is unclear but centers around the claim that intraperitoneal infection of large amounts of the virus must infect another cell type other than just B cells for establishment of latency. (1)

Conclusion

Overall paper length should be 3,000 words, with at least 3 figures.

References

Edited by student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 238 Microbiology, 2009, Kenyon College.