Magnetotactic Bacteria

Introduction to Magnetotactic Bacteria

History and Significance

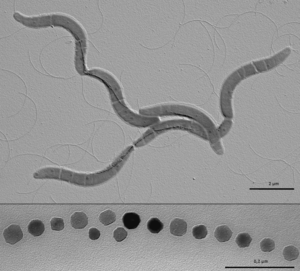

Magnetotactic bacteria (MB) are gram-negative bacteria that build specialized organelles called magnetosomes in order to store magnetic material and align themselves with the earth’s magnetic field. Magnetotactic bacteria were first described in 1975 when Richard Blakemore realized that a specific group of bacteria collected from sediment constantly swam in the same geographic direction, regardless of the positioning of the microscope or external stimuli.[1] MB are mostly found in shallow aquatic environments where oxygen and other redox compounds are horizontally stratified. Many described magnetotactic bacteria localize at or close to the oxic anoxic transition zone (OATZ)—a region in the water column that has very low oxygen levels. [2] The current model (shown in Figure 1) to explain the selective advantage provided by magnetosomes is that magnetotactic bacteria are able to locate the OATZ much easier than bacteria that solely use chemotactic and aerotactic mechanisms. [3] Although the magneto-aerotaxis model has been widely accepted amongst the scientific community, new research is suggesting that the behavior magnetotactic bacteria exhibit in the environment may be more complicated than a simple response to oxygen levels:

- Some MB species also show phototactic response, which helps reinforce magneto-aerotactic behavior and repel them from surface waters [4, 5]

- Genome sequences show that MB have some of the highest numbers of signaling proteins of Bacteria [6]

- MB produce more magnetosomes than necessary to align with the earth’s magnetic field [7]

- MB have been found near the equator, where their magneto-aerotactic behavior has no advantage [8]

Regardless of the actual biological function of magnetosomes, magnetotactic bacteria are a very interesting research topic because they have the potential to impact a large number of scientific and applied disciplines. Magnetosomes are the perfect model for the study of cellular compartmentalization and organization in bacteria because the formation of specialized, membrane bound, features is usually attributed to eukaryotic organisms. Magnetotactic bacteria are also a great model for the study of biomineralization because of the precise control over the composition, size and morphology of magenetite crystals in magnetosomes.

Magnetosome Island

Bacterial genomes can evolve over time due to mutations, rearrangements, or horizontal gene transfer and many genes that are acquired through horizontal gene transfer come in blocks that are recognized as genomic islands. These genomic islands can be recognized by nucleotide statistics (GC skew) that differ from the rest of the organisms DNA and are often associated with inserted tRNA genes, pseudogenes, transposons, and IS elements.[9] The gene clusters encoding the majority of magnetosome proteins have many hallmarks of genomic islands and, as a result, have been termed the magnetosome gene island (MAI).[10] Research suggests that specific mechanisms may be in place to delete the MAI under stressful conditions because of the large energetic burden it creates for the organism.

Ubiquity of the Magnetosome Island

Evolution of the Magnetosome Island

MAI genes are required in multiple steps of magnetosome formation. Phylogenetic comparisons of magnetotactic bacteria use the highly conserved mam genes to trace the evolutionary history of magnetosome formation. MAI genes have been found in some of the most evolutionarily diverse species of magnetotactic bacteria, and there are multiple interpretations of what this could mean in terms of the evolution of magnetosome formation:[11]

- magnetosome formation was invented only once during evolution

- magnetosome genes spread to diverse bacterial clades through ancient horizontal gene transfer

- the last common ancestor of the Proteobacteria and the Nitrospira may have been magnetotactic bacteria and many species of the two groups lost their magnetosome genes over time

Magnetosome Formation

Identification of the genetic elements needed for magnetosome formation took many years due the lack of cultured and genetically tractable model organisms. Aquaspirillum magnetotacticum, now referred to as Magnetospirillum magnetotacticum, or MS-1, was the first magnetotactic bacteria to be isolated in pure culture. Two closely related Magnetospirillum species, Magnetospirillum grysphiswaldense (MSR-1) and Magnetospirillum magneticum (AMB-1), were isolated soon after and have become the focus of most magnetosome formation research.[12,13] Three approaches have been used to determine the molecular factors involved in the formation of magnetosomes: proteomics, genetic analysis, and comparative genomics.

Membrane Biogenesis and Protein Sorting

Chain Formation

Biomineralization

Biomineralization is the process in which organisms produce minerals, usually for some biological function. Magnetotactic bacteria form magnetosomes in order to provide a compartment to safely and efficiently direct the formation of magnetite crystals. The first step in magnetite biomineralization is the transport of iron into the cell.

Research Applications

Bioremediation

Conventional methods of remediation such as chemical precipitation, ion exchange, and active carbon adsorption have been used to clean up contaminated sites, but these methods are commonly associated with high costs, low efficiency, and problems with secondary pollution.

Barriers

References

[1] Blakemore, R. (1975). Magnetotactic bacteria. Science (New York, N.Y.), 190(4212), 377-379.

Further Reading

Edited by Kelsey Waite, a student of Suzanne Kern in BIOL168L (Microbiology) in The Keck Science Department of the Claremont Colleges. Spring 2015.