Role of the Lux Operon in Bioluminescence

Introduction

The lux operon has long been studied for its unique gene product: bioluminescence. Found in the bacterium Vibrio fischeri, the lux operon is an essential part of the bacterium's genetic code. In fact, the bacterial bioluminescence produced by the Vibrio fischeri bacteria plays an essential role in many mutualistic relationships with other organisms. One such organism is the Hawaiian Bobtail Squid (Euprymna scolopes).

The relationship that exists between the Hawaiian Bobtail Squid and its bacterial partner Vibrio fischeri is mutually beneficial, as the glowing bacteria are provided with shelter inside of the squid’s light organ, and the squid uses the bacterium’s bioluminescent properties as camouflage. By allowing the underside of its body to glow (as shown to the left), the Hawaiian Bobtail Squid effectively eliminates its own shadow, which in turn makes it less visible to any potential predators.

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Microbiome

Include some current research, with at least one image.

Genetics

The mechanism that allows the Hawaiian Bobtail Squid to glow at night but not during the day is actually a result of gene expression in the bacteria, more specifically expression of the lux operon.

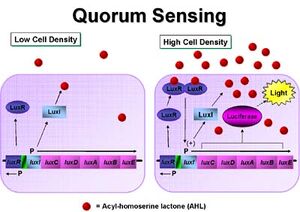

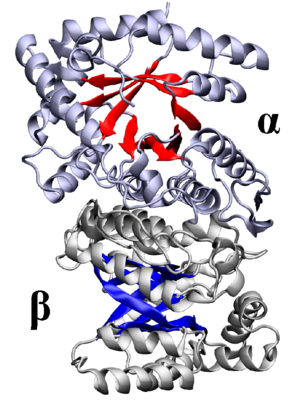

At night, abundant AHL molecules bind to the transcription factor luxR, which regulates gene expression of the operon. The newly bound complex moves and binds to the lux box, changing the secondary structure of the complex. This change allows the RNA polymerase to stay on the gene and transcribe all of the genes contained in the operon. The genes luxA and luxB produce the alpha and beta subunits of the luciferase enzyme, respectively. Luciferase is the enzyme responsible for bioluminescence in the bacteria Vibrio fischeri, as well as in many other bioluminescent organisms.

Conversely, during the day the squid limits light production by the bacteria. Low levels of AHL within the squid’s light organ cause RNA polymerase to bind to the promoter, transcribing luxR. Then, RNA polymerase binds to the other promoter and transcribes the luxI gene, producing LuxI as a result. LuxI binds to the substrate to catalyze the production of AHL, then RNA polymerase falls off of the strand. This means that AHL is constantly produced, allowing the levels of AHL to increase until the bioluminescent properties of the bacteria become useful to the squid after dark, and the squid begins to glow again.

Conclusion

Overall text length (all text sections) should be at least 1,000 words (before counting references), with at least 2 images.

Include at least 5 references under References section.

References

Edited by Lauren Lehr, student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 116 Information in Living Systems, 2021, Kenyon College./

- ↑ Swartzman, A., Shalini Kapoor, A. F. Graham, and EDWARD A. Meighen. "A new Vibrio fischeri lux gene precedes a bidirectional termination site for the lux operon." Journal of bacteriology 172, no. 12 (1990): 6797-6802.

- ↑ Lyell, Noreen L., Anne K. Dunn, Jeffrey L. Bose, and Eric V. Stabb. "Bright mutants of Vibrio fischeri ES114 reveal conditions and regulators that control bioluminescence and expression of the lux operon." Journal of bacteriology 192, no. 19 (2010): 5103-5114.

- ↑ Xu, Tingting, Steven Ripp, Gary S. Sayler, and Dan M. Close. "Expression of a humanized viral 2A-mediated lux operon efficiently generates autonomous bioluminescence in human cells." PloS one 9, no. 5 (2014): e96347.

- ↑ Verma, Subhash C., and Tim Miyashiro. 2013. "Quorum Sensing in the Squid-Vibrio Symbiosis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14, no. 8: 16386-16401. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms140816386