Acinetobacter baumannii: The Emergence of a Dangerous Multidrug-Resistant Pathogen

By: Kerri-Lynn Conrad

Introduction

Genome Structure

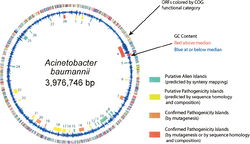

The genome of Acinetobacter baumannii contains 3,976,746 base pairs and is composed of 3830 open reading frames. Approximately 17.2% of the open-reading frames are located within putative alien islands, highlighting Acinetobacter baumannii’s remarkable ability to incorporate foreign DNA into its genome (1).

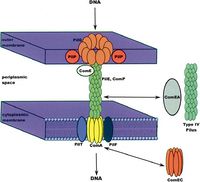

Acinetobacter baumannii has several genes that permit it to pick up foreign DNA from its environment, as well as other microbes. These genes include PilQ, ComE, and PilF, commonly found in gram-negative bacteria, as well as closely related species Acinetobacter baylyi. Interestingly, the genome of Acinetobacter baumannii lacks a gene for ComP, a gene for a membrane transporter important for foreign DNA uptake in many species. Nonetheless, the ComEA gene of A. baumannii codes for a transmembrane protein that can bind foreign DNA in the environment and transport it to the internal environment of the cell where it can be incorporated into the genome. One study has suggested that the ComEA gene or possibly even the type IV pilus of A. baumannii allow it to effectively obtain foreign DNA from the environment, thus eliminating the need for the ComP gene found in many other species (1).

Closely tied to A. baumanniii’s ability to obtain foreign DNA for incorporation into its own genome are the putative alien islands (pAs) that permit the pathogenicity of A. baumanniii, distinguishing it from other Acinetobacter species. pAs obtained from the environment or from other species can possess a variety of functions. Nevertheless, many of the pAs that remain preserved in the A. baumanniigenome are responsible for pathogenic and virulence factors, and are deemed PAIs. Of the approximately 28 pAs in the A. baumannii genome, 12 share significant sequence identity with virulence genes in other species of bacteria. The largest of these PAIs is a 133,740 base pair island containing several transposons, integrases, and eight genes with significant sequence homology to Legionella/Coxiella Type IV virulence/secretion apparatus (1). Seven of the twelve PAIs contain genes that encode proteins or efflux pumps that confer drug resistance to A. baumanniii, although many strains of A. baumanniidevelop additional drug resistance genes through the evolutionary pressures of treatment with pharmaceuticals (1).

In addition to the virulence-conferring genes of the A. baumannii PAIs, the pAs obtained by the bacterium from the outside environment include genes for heavy metal resistance, iron metabolism, quorum sensing capabilities, lipid metabolism, amino acid uptake, and genes for the breakdown of xenobiotics (1).

Of paramount importance to the pathogenic potential of A. baumannii are the plethora of antibiotic resistance genes contained within its genome. The AYE strain of A. baumannii has a 86,190 base pair PAI inserted into its genome that contains 45 of its 52 drug resistance genes (2). Similarly, a more recent isolate, the ATCC17978 strain of A. baumannii contains a 13,277 base pair PAI that contains 74 drug resistance genes, 32 efflux pumps, 11 genes related to drug/metabolite transporters (DMTs), as well as 26 genes encoding resistance to a variety of heavy metals, including copper, cadmium, zinc, and arsenic (1). The drug resistance genes on the PAI of this strain confer resistance to several classes of antibiotics, including β -lactams, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and rifampin (2). Genomic comparisons of the AYE and ATCC17978 A. baumannii strains suggest that the ATCC17978 strain has disposed of some of the drug resistance genes observed in the AYE strain in order to evolve a potent drug resistance cassette observed in its genomically inserted PAI (1). It is clear from these genomic analyses that the ability to obtain foreign DNA from environmental sources has proven immensely important in the development of A. baumannii pathogenesis. It is likely that this pathogen will continue to optimize its virulent potential through the attainment, integration, and use of foreign genes.

Cell Structure

Metabolism

Epidemiology

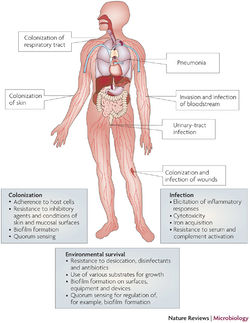

Pathology

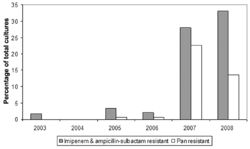

Multidrug-Resistance

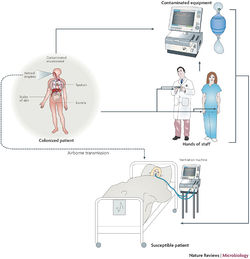

Implications for Hospitals

Outbreak in United States Military Treatment Facilities

Future Work

References

1 Dominguez, G., Dambaugh, T. R., Stamey, F. R., Dewhurst, S., Inoue, N. & Pellett, P. E. 1999. Human herpesvirus 6B genome sequence:

coding content and comparison with human herpesvirus 6A. J Virol 73:8040–8052.

2 Gompels, U. A., Nicholas, J., Lawrence, G., Jones, M., Thomson, B. J., Martin, M. E., Efstathiou, S., Craxton, M. & Macaulay, H. A. 1995. The DNA sequence of human herpesvirus-6: structure, coding content, and genome evolution. Virology 209:29–51.

3 Braun, D. K., Pellett, P. E., Hanson C. A. 1995. Presence and expression of human herpesvirus 6 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of S100-positive, T cell chronic lymphoproliferative disease. J. Infect. Dis. 171:1351–1355.

4 Meyne, J., Ratliff, R. L., Moyzis, R. K. 1989. Conservation of the human telomere sequence (TTAGGG)n among vertebrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.USA 86:7049–7053.

5 Clark, D. A. 2000. Human herpesvirus 6. Rev Med Virol 10:155–173

6 Mendez J.C., Dockrell, D.H., Espy, M.J., Smith, T.F., Wilson, J.A., Harmsen, W.S., Ilstrup, D., Paya, C.V. 2001. Human beta-herpesvirus interactions in solid organ transplant recipients. J Infect Dis 183(2):179-184.

7 Nicholas, J., Martin M.E. 1994. Nucleotide sequence analysis of a 38.5-kilobase-pair region of the genome of human herpesvirus 6 encoding human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene homologs and transactivating functions. J. Virol. 68:597–610

8 Dockrell, D. H. 2003. Human herpesvirus 6: molecular biology and clinical features. J. Med. Microbiol. 52:5–18.

9 Zou, P., Isegawa, Y., Nakano, K., Haque, M., Horiguchi, Y., Yamanishi, K. 1999. Human herpesvirus 6 open reading frame U83 encodes a functional chemokine. J Virol 73:5926–5933.

10 Rotola, A., Ravaioli, T., Gonelli, A., Dewhurst, S., Cassai, E. & DiLuca, D. 1998. U94 of human herpesvirus 6 is expressed in latently infected peripheral blood mononuclear cells and blocks viral gene expression in transformed lymphocytes in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:13911–13916.

11 Chou, S., Marousek G. I. 1994. Analysis of interstrain variation in a putative immediate-early region of human herpesvirus 6 DNA and definition of variant-specific sequences. Virology 198:370–376.

12 Bolle, L.D., Naesens L., Erik, D.C. 2005. Update on human herpesvirus 6 biology, clinical features, and therapy, Clin Microbiol Rev 18:217–245.

13 Brown, N. A., Sumaya, C. V., Liu, C.-R., Ench, Y., Kovacs, A., Coronesi, M., Kaplan, M. H. 1988. Fall in human herpesvirus 6 seropositivity with age. Lancet ii, 396.

14 Ranger S., Patillaud S., Denis F., Himmich A., Sangare A., M'Boup S. 1991.Seroepidemiology of human herpesvirus-6 in pregnant women from different parts of the world. J Med Virol 34:194-8.

15 Enders, G., Biber, M., Meyer, G., Helftenbein, E. 1990. Prevalence of antibodies to human herpesvirus 6 in different age groups, in children with exanthema subitum, other acute exanthematous childhood diseases, Kawasaki syndrome, and acute infections with other herpesviruses and HIV. Infection 18:12–15.

16 Wang, F. Z., Dahl, H., Ljungman, P., Linde, A. 1999. Lymphoproliferative responses to human herpesvirus-6 variant A and variant B in healthy adults. J. Med. Virol. 57:134–139.

17 Collot, S., Petit, B., Bordessoule, D., Alain, S., Touati, M., Denis, F., Ranger-Rogez, S. 2002. Real-time PCR for quantification of human herpesvirus 6 DNA from lymph nodes and saliva. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2445–2451.

18 van Loon, N. M., Gummuluru, S., Sherwood, D. J., Marentes, R., Hall, C. B. & Dewhurst, S. 1995. Direct sequence analysis of human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) sequences from infants and comparison of HHV-6 sequences from mother/infant pairs. Clin Infect Dis 21:1017–1019.

19 Portolani M., Cermelli C., Moroni A. 1993. Human herpesvirus-6 infections in infants admitted to hospital. J. Med.Virol. 39:146–51

20 Pruksananonda, P., Hall, C.B., Insel, R.A., McIntyre, K., Pellett, P.E., Long, C. E., Schnabel, K. C., Pincus, P. H., Stamey, F. R., Dambaugh, T. R. 1992. Primary human herpesvirus 6 infection in young children. N. Engl. J. Med. 326:1445–1450.

21 Stoeckle M.Y. The spectrum of human herpesvirus 6 infection: from roseola infantum to adult disease. Annu Rev Med 2000: 51: 423–430.

22 Di Luca, D., Mirandola, P., Ravaioli, T., Bigoni, B., Cassai, E. Distribution of HHV-6 variants in human tissues. Infectious Agents and Disease 1996;5:203-14.

23 Luppi, M., Barozzi, P., Morris, C.M., Merelli, E., Torelli, G. 1998. Integration of human herpesvirus 6 genome in human chromosomes. Lancet 352:1707-8.

24 Lusso, P., Gallo, R.C. 1995. Human herpesvirus 6 in AIDS. Immunol Today 16:67-71.

25 Nacheva, E.P., Ward, K.N., Brazma, D., Virgili, A., Howard, J., Leong, H.N., Clark, D.A. 2008. Human herpesvirus 6 integrates within telomeric regions as evidenced by five different chromosomal sites. Journal of Medical Virology, 80:1952–1958.

26 Hall, C.B., Caserta, M.T., Schnabel, K., Shelley, L.M., Marino, A.S., Carnahan, J.A. 2008. Chromosomal integration of human herpesvirus 6 is the major mode of congenital human herpesvirus 6 infection. Pediatrics 122(3): 513–520.

27 Ward, K.N., Leong, H.N., Nacheva, E.P., Howard, J., Atkinson, C.E., Davies, N.W., Griffiths, P.D., Clark, D.A. 2006. Human herpesvirus 6 chromosomal integration in immunocompetent patients results in high levels of viral DNA in blood, sera, and hair follicles. J Clin Microbiol 44:1571–1574.

28 Gompels, U. A., Macaulay, H.A. 1995. Characterization of human telomeric repeat sequences from human herpesvirus 6 and relationship to replication. J. Gen. Virol. 76:451-458.

29 Arbuckle, J.H., Medveczky, M.M., Luka, J., Hadley, S.H., Luegmayr, A., Ablashi, D., Lund, T.C., Tolar, J., DeMeirleir, K., Montoya, J.G., Komaroff, A.L., Ambros, P.F., Medveczky, P.G. 2010. The latent human herpesvirus-6A genome specifically integrates in telomeres of human chromosomes in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 107:5563–5568.

30 Daibata, M., Taguchi, T., Taguchi, H., Miyoshi, I. 1998.Integration of human herpesvirus 6 in a Burkitt's lymphoma cell line. Br J Haematol 102:1307-1313

31 Kishi, M., Harada, H., Takahashi, M., Tanada, A., Hayashi, M., Nonoyama, M., Josephs, S.F., Buchbinder, A., Schachter, F., Ablashi, D., Wong-Staal, F., Salahuddin, S.Z., Gallo, R.C. 1988. A repeat sequence, GGGTTA, is shared by DNA of human herpesvirus 6 and Marek’s disease virus. J. Virol. 62:4824–4827.

32 Tanaka-Taya, K., Sashihara, J., Kurahashi, H., Amo, K., Miyagawa, H., Kondo, K., Okada, S., Yamanishi, K. 2004. Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) is transmitted from parent to child in an integrated form and characterization of cases with chromosomally integrated HHV-6 DNA. J Med Virol 73:465-473.

33 Daibata, M., Taguchi, T., Nemoto, Y., Taguchi, H., Miyoshi, I. Inheritance of chromosomally integrated human herpesvirus 6 DNA. Blood 1999; 94:1545-1549.

34 Ablashi, D.V., Eastman, H.B., Owen, C.B., Roman, M.M., Friedman, J., Zabriskie, J.B., Peterson, D.L., Pearson, G.R., Whitman, J.E. 2003. Cross-reactivity with myelin basic protein and human herpesvirus-6 in multiple sclerosis. Annu Neurol. 53(2): 189–197.

Edited by Kerri-Lynn Conrad, student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 238 Microbiology, 2011, Kenyon College.