Acinetobacter baumannii: The Emergence of a Dangerous Multidrug-Resistant Pathogen

By: Kerri-Lynn Conrad

Introduction

Genome Structure

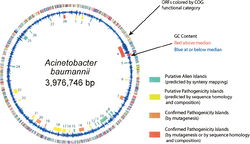

The genome of Acinetobacter baumannii is a singular circular chromsome, accompanied by two plasmids, though this number can vary depending on the strain (3). The genome contains 3,976,746 base pairs and is composed of 3830 open reading frames. Approximately 17.2% of the open-reading frames are located within putative alien islands, highlighting Acinetobacter baumannii’s remarkable ability to incorporate foreign DNA into its genome (1).

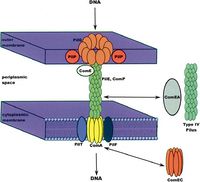

Acinetobacter baumannii has several genes that permit it to pick up foreign DNA from its environment, as well as other microbes. These genes include PilQ, ComE, and PilF, commonly found in gram-negative bacteria, as well as closely related species Acinetobacter baylyi. Interestingly, the genome of Acinetobacter baumannii lacks a gene for ComP, a gene for a membrane transporter important for foreign DNA uptake in many species. Nonetheless, the ComEA gene of A. baumannii codes for a transmembrane protein that can bind foreign DNA in the environment and transport it to the internal environment of the cell where it can be incorporated into the genome. One study has suggested that the ComEA gene or possibly even the type IV pilus of A. baumannii allow it to effectively obtain foreign DNA from the environment, thus eliminating the need for the ComP gene found in many other species (1).

Closely tied to A. baumanniii’s ability to obtain foreign DNA for incorporation into its own genome are the putative alien islands (pAs) that permit the pathogenicity of A. baumanniii, distinguishing it from other Acinetobacter species. pAs obtained from the environment or from other species can possess a variety of functions. Nevertheless, many of the pAs that remain preserved in the A. baumanniigenome are responsible for pathogenic and virulence factors, and are deemed PAIs. Of the approximately 28 pAs in the A. baumannii genome, 12 share significant sequence identity with virulence genes in other species of bacteria. The largest of these PAIs is a 133,740 base pair island containing several transposons, integrases, and eight genes with significant sequence homology to Legionella/Coxiella Type IV virulence/secretion apparatus (1). Seven of the twelve PAIs contain genes that encode proteins or efflux pumps that confer drug resistance to A. baumanniii, although many strains of A. baumanniidevelop additional drug resistance genes through the evolutionary pressures of treatment with pharmaceuticals (1).

In addition to the virulence-conferring genes of the A. baumannii PAIs, the pAs obtained by the bacterium from the outside environment include genes for heavy metal resistance, iron metabolism, quorum sensing capabilities, lipid metabolism, amino acid uptake, and genes for the breakdown of xenobiotics (1).

Of paramount importance to the pathogenic potential of A. baumannii are the plethora of antibiotic resistance genes contained within its genome. The AYE strain of A. baumannii has a 86,190 base pair PAI inserted into its genome that contains 45 of its 52 drug resistance genes (2). Similarly, a more recent isolate, the ATCC17978 strain of A. baumannii contains a 13,277 base pair PAI that contains 74 drug resistance genes, 32 efflux pumps, 11 genes related to drug/metabolite transporters (DMTs), as well as 26 genes encoding resistance to a variety of heavy metals, including copper, cadmium, zinc, and arsenic (1). The drug resistance genes on the PAI of this strain confer resistance to several classes of antibiotics, including β -lactams, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and rifampin (2). Genomic comparisons of the AYE and ATCC17978 A. baumannii strains suggest that the ATCC17978 strain has disposed of some of the drug resistance genes observed in the AYE strain in order to evolve a potent drug resistance cassette observed in its genomically inserted PAI (1). It is clear from these genomic analyses that the ability to obtain foreign DNA from environmental sources has proven immensely important in the development of A. baumannii pathogenesis. It is likely that this pathogen will continue to optimize its virulent potential through the attainment, integration, and use of foreign genes.

Cell Structure

A. baumannii is a gram-negative, non-motile, rod-shaped bacterium. Like other species of Acinetobacter, A. baumannii contains a cell envelope with multiple layers, including an outer membrane and inner cytoplasmic membrane separated by a layer of periplasmic space (4).

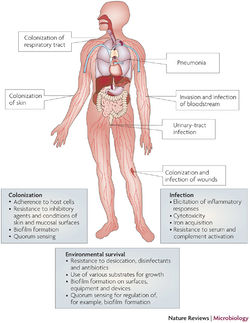

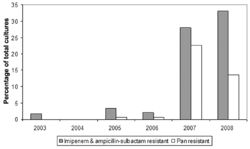

Unique to A. baumannii is the small amount of porins in the cell membrane. In bacterial cells, porins allow for the transport of various molecules across the lipid membrane. Various cellular functions and consequences have been attributed to the presence of porins in the membrane, some helpful and others detrimental to subsistence. In some cases, porins can permit cells to adhere to other bacterial cells (such as in the formation of biofilms). Nonetheless, porins can allow the entry of antibiotic and other antimicrobial compounds across the cell membrane and into the cytoplasm, where they disrupt normal enzymatic processes or destroy cellular structures and organelles (5). The decreased porin expression observed in A. baumannii has been viewed as another mechanism by which this pathogen sustains resistance to antibiotics and antimicrobial agents, by simply preventing these compounds from entering the cell. For example, A. baumannii has been able to become resistant to imipenem and carbapenem antibiotics by eliminating several porins, including porin CarO, as well as another porin that seems to share significant sequence homology with the OprD porin found in other gram negative bacteria (6,7).

In addition to porins, the scattered in the membrane of A. baumannii are efflux pumps that allow for the removal of organic compounds, as well as antibiotic or antimicrobial agents that could prove detrimental to the cell. There are several classes of efflux pumps, however, the majority of drug efflux pumps found in A. baumannii belong to either the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) or the Resistance-Nodulation-Division (RND) family. These efflux pumps operate by proton motive force expulsion (5).

Also found in the cell membrane of A. baumannii are protein channels and transporters involved in the uptake of foreign DNA. Located in the outer membrane is PilQ, which allows initial entry of foreign DNA. The DNA is then bound by ComE, and is transported through the periplasmic space by PilE, or the type IV pilus to the ComA transmembrane protein located in the inner membrane. Transport through ComA allows the DNA to enter the cytoplasm of A. baumannii. Once inside the cell, this foreign DNA is either degraded, integrated into the genome, or exists as a plasmid (1).

Of particular interest with regard to the cellular structure of A. baumannii is the bacteria’s outer membrane protein A (OmpA). OmpA has been associated with the ability of A. baumannii to form biofilms on both biological surfaces such as the human skin, as well as abiotic environments such as catheters and shunts (8). Furthermore, OmpA is believed to be a major component of the mechanism by which A. baumannii invades epithelial cells. OmpA allows A. baumannii to adhere and invade epithelial cells by a zipper-like mechanism that involves the motion of both microtubules and microfilaments (9).

Metabolism

A. baumannii are aerobic, non-fermentative, catalase-positive and oxidase-negative bacteria (10). Like other A. baumannii species, they are unable to reduce nitrate to nitrite. They obtain nitrogen from ammonium and nitrate salts. They are able to use various organic compounds for metabolism and energy production, including sugars, fatty acids, some amino acids, unbranched hydrocarbon chains, and some aromatic compounds (including aromatic amino acids). The use of sugars as a carbon source for metabolic pathways by A. baumannii is restricted to D-glucose, D-ribose, D-xylose, and L-arabinose (4).

D-glucose is metabolized by A. baumannii through the Etner-Doudoroff pathway. Pentoses used by A. baumannii in metabolism are degraded by an aldose dehydrogenase. The oxidized pentoic acids are then converted to α-ketoglutarate through several steps involving dehydration and dehydrogenation mechanisms (4).

The tri-carboxylic acid cycle in A. baumannii is similar to cycles observed in other proteobacteria. Several of the enzymes involved in TCA cycle steps have been purified from A. baumannii. The bacterium’s citrate synthase is composed of four identical subunits. A. baumannii’s aconitase has been shown to form glyoxylate from a citrate substrate. In addition to these enzymes, two NADP linked isocitrate dehydrogenases have been isolated, and are induced by glyoxylate or pyruvate. Finally, the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex of A. baumannii functions as it does in the TCA cycle of other organisms, with ATP exhibiting an inhibitory effect on the action of the complex, whereas ADP or AMP increase its activity and appropriately lower the Km of the enzyme (4).

A. baumannii can degrade aromatic compounds through the β-ketoadipate pathway, involving β-ketoadipate enol-lactone hydrolase and β-ketoadipate succinyl -CoA transferase as the primary metabolizing enzymes. Through this pathway, aromatic compounds are ultimately converted to succinic acid and acetyl-CoA (4).

The oxidase-negative nature of A. baumannii indicates that the bacterium does not have a cytochrome c component of its electron transport system. However, A. baumannii does use the cytochrome system in its electron transport pathways, demonstrated by complete inhabitation of NADH oxidase activity when the cells were treated with cyanide. Cytochrome a1, cytochrome a2, cytochrome b1, as well as flavin have been shown to play a role in the electron transport pathways and cellular respiration of A. baumannii (4).

In nucleic acid metabolism, A. baumannii must use uracil as pyrimidine in both RNA and DNA synthesis. Because A. baumannii lacks the thymine phosphorylase and thymidine kinase enzymes, it cannot incorporate thymine into DNA molecules (4).

Epidemiology

Pathology

Multidrug-Resistance

Implications for Hospitals

Outbreak in United States Military Treatment Facilities

Future Work

References

1 Dominguez, G., Dambaugh, T. R., Stamey, F. R., Dewhurst, S., Inoue, N. & Pellett, P. E. 1999. Human herpesvirus 6B genome sequence:

coding content and comparison with human herpesvirus 6A. J Virol 73:8040–8052.

2 Gompels, U. A., Nicholas, J., Lawrence, G., Jones, M., Thomson, B. J., Martin, M. E., Efstathiou, S., Craxton, M. & Macaulay, H. A. 1995. The DNA sequence of human herpesvirus-6: structure, coding content, and genome evolution. Virology 209:29–51.

3 Braun, D. K., Pellett, P. E., Hanson C. A. 1995. Presence and expression of human herpesvirus 6 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of S100-positive, T cell chronic lymphoproliferative disease. J. Infect. Dis. 171:1351–1355.

4 Meyne, J., Ratliff, R. L., Moyzis, R. K. 1989. Conservation of the human telomere sequence (TTAGGG)n among vertebrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.USA 86:7049–7053.

5 Clark, D. A. 2000. Human herpesvirus 6. Rev Med Virol 10:155–173

6 Mendez J.C., Dockrell, D.H., Espy, M.J., Smith, T.F., Wilson, J.A., Harmsen, W.S., Ilstrup, D., Paya, C.V. 2001. Human beta-herpesvirus interactions in solid organ transplant recipients. J Infect Dis 183(2):179-184.

7 Nicholas, J., Martin M.E. 1994. Nucleotide sequence analysis of a 38.5-kilobase-pair region of the genome of human herpesvirus 6 encoding human cytomegalovirus immediate-early gene homologs and transactivating functions. J. Virol. 68:597–610

8 Dockrell, D. H. 2003. Human herpesvirus 6: molecular biology and clinical features. J. Med. Microbiol. 52:5–18.

9 Zou, P., Isegawa, Y., Nakano, K., Haque, M., Horiguchi, Y., Yamanishi, K. 1999. Human herpesvirus 6 open reading frame U83 encodes a functional chemokine. J Virol 73:5926–5933.

10 Rotola, A., Ravaioli, T., Gonelli, A., Dewhurst, S., Cassai, E. & DiLuca, D. 1998. U94 of human herpesvirus 6 is expressed in latently infected peripheral blood mononuclear cells and blocks viral gene expression in transformed lymphocytes in culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:13911–13916.

11 Chou, S., Marousek G. I. 1994. Analysis of interstrain variation in a putative immediate-early region of human herpesvirus 6 DNA and definition of variant-specific sequences. Virology 198:370–376.

12 Bolle, L.D., Naesens L., Erik, D.C. 2005. Update on human herpesvirus 6 biology, clinical features, and therapy, Clin Microbiol Rev 18:217–245.

13 Brown, N. A., Sumaya, C. V., Liu, C.-R., Ench, Y., Kovacs, A., Coronesi, M., Kaplan, M. H. 1988. Fall in human herpesvirus 6 seropositivity with age. Lancet ii, 396.

14 Ranger S., Patillaud S., Denis F., Himmich A., Sangare A., M'Boup S. 1991.Seroepidemiology of human herpesvirus-6 in pregnant women from different parts of the world. J Med Virol 34:194-8.

15 Enders, G., Biber, M., Meyer, G., Helftenbein, E. 1990. Prevalence of antibodies to human herpesvirus 6 in different age groups, in children with exanthema subitum, other acute exanthematous childhood diseases, Kawasaki syndrome, and acute infections with other herpesviruses and HIV. Infection 18:12–15.

16 Wang, F. Z., Dahl, H., Ljungman, P., Linde, A. 1999. Lymphoproliferative responses to human herpesvirus-6 variant A and variant B in healthy adults. J. Med. Virol. 57:134–139.

17 Collot, S., Petit, B., Bordessoule, D., Alain, S., Touati, M., Denis, F., Ranger-Rogez, S. 2002. Real-time PCR for quantification of human herpesvirus 6 DNA from lymph nodes and saliva. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2445–2451.

18 van Loon, N. M., Gummuluru, S., Sherwood, D. J., Marentes, R., Hall, C. B. & Dewhurst, S. 1995. Direct sequence analysis of human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) sequences from infants and comparison of HHV-6 sequences from mother/infant pairs. Clin Infect Dis 21:1017–1019.

19 Portolani M., Cermelli C., Moroni A. 1993. Human herpesvirus-6 infections in infants admitted to hospital. J. Med.Virol. 39:146–51

20 Pruksananonda, P., Hall, C.B., Insel, R.A., McIntyre, K., Pellett, P.E., Long, C. E., Schnabel, K. C., Pincus, P. H., Stamey, F. R., Dambaugh, T. R. 1992. Primary human herpesvirus 6 infection in young children. N. Engl. J. Med. 326:1445–1450.

21 Stoeckle M.Y. The spectrum of human herpesvirus 6 infection: from roseola infantum to adult disease. Annu Rev Med 2000: 51: 423–430.

22 Di Luca, D., Mirandola, P., Ravaioli, T., Bigoni, B., Cassai, E. Distribution of HHV-6 variants in human tissues. Infectious Agents and Disease 1996;5:203-14.

23 Luppi, M., Barozzi, P., Morris, C.M., Merelli, E., Torelli, G. 1998. Integration of human herpesvirus 6 genome in human chromosomes. Lancet 352:1707-8.

24 Lusso, P., Gallo, R.C. 1995. Human herpesvirus 6 in AIDS. Immunol Today 16:67-71.

25 Nacheva, E.P., Ward, K.N., Brazma, D., Virgili, A., Howard, J., Leong, H.N., Clark, D.A. 2008. Human herpesvirus 6 integrates within telomeric regions as evidenced by five different chromosomal sites. Journal of Medical Virology, 80:1952–1958.

26 Hall, C.B., Caserta, M.T., Schnabel, K., Shelley, L.M., Marino, A.S., Carnahan, J.A. 2008. Chromosomal integration of human herpesvirus 6 is the major mode of congenital human herpesvirus 6 infection. Pediatrics 122(3): 513–520.

27 Ward, K.N., Leong, H.N., Nacheva, E.P., Howard, J., Atkinson, C.E., Davies, N.W., Griffiths, P.D., Clark, D.A. 2006. Human herpesvirus 6 chromosomal integration in immunocompetent patients results in high levels of viral DNA in blood, sera, and hair follicles. J Clin Microbiol 44:1571–1574.

28 Gompels, U. A., Macaulay, H.A. 1995. Characterization of human telomeric repeat sequences from human herpesvirus 6 and relationship to replication. J. Gen. Virol. 76:451-458.

29 Arbuckle, J.H., Medveczky, M.M., Luka, J., Hadley, S.H., Luegmayr, A., Ablashi, D., Lund, T.C., Tolar, J., DeMeirleir, K., Montoya, J.G., Komaroff, A.L., Ambros, P.F., Medveczky, P.G. 2010. The latent human herpesvirus-6A genome specifically integrates in telomeres of human chromosomes in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 107:5563–5568.

30 Daibata, M., Taguchi, T., Taguchi, H., Miyoshi, I. 1998.Integration of human herpesvirus 6 in a Burkitt's lymphoma cell line. Br J Haematol 102:1307-1313

31 Kishi, M., Harada, H., Takahashi, M., Tanada, A., Hayashi, M., Nonoyama, M., Josephs, S.F., Buchbinder, A., Schachter, F., Ablashi, D., Wong-Staal, F., Salahuddin, S.Z., Gallo, R.C. 1988. A repeat sequence, GGGTTA, is shared by DNA of human herpesvirus 6 and Marek’s disease virus. J. Virol. 62:4824–4827.

32 Tanaka-Taya, K., Sashihara, J., Kurahashi, H., Amo, K., Miyagawa, H., Kondo, K., Okada, S., Yamanishi, K. 2004. Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) is transmitted from parent to child in an integrated form and characterization of cases with chromosomally integrated HHV-6 DNA. J Med Virol 73:465-473.

33 Daibata, M., Taguchi, T., Nemoto, Y., Taguchi, H., Miyoshi, I. Inheritance of chromosomally integrated human herpesvirus 6 DNA. Blood 1999; 94:1545-1549.

34 Ablashi, D.V., Eastman, H.B., Owen, C.B., Roman, M.M., Friedman, J., Zabriskie, J.B., Peterson, D.L., Pearson, G.R., Whitman, J.E. 2003. Cross-reactivity with myelin basic protein and human herpesvirus-6 in multiple sclerosis. Annu Neurol. 53(2): 189–197.

Edited by Kerri-Lynn Conrad, student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 238 Microbiology, 2011, Kenyon College.