Chicken Anemia Virus and Depression

A Viral Biorealm page on the family Chicken Anemia Virus and Depression

Baltimore Classification

Group II: single-stranded DNA viruses

Higher order categories

Kingdom: Virus

Family: Circoviridae

Genus: Gyrovirus

Description and Significance

Chicken Anemia Virus (CAV), is the cause of a disease refered to as called Blue Wing Disease, Infectious Chicken Anemia, and Chicken Anemia Agent. Afflicted birds lose bone marrow density, become anemic, and have suppressed immune systems. It is a vertically transmitted circovirus, usually from a parent flock. Thanks to widespread vaccination, the clinical disease is uncommon today. Subclinical infection, where birds are asymptomatically carrying the virus, still occurs often [3].

Symptoms of CAV include pale extremeties such as wattle, comb and legs, anorexia, weakness, cyanosis, lethargy and sudden death. Neurological symptoms include dullness, depression, and paresis. Severely sick birds may die within 2 to 4 weeks, while survivors are usually stunted [1].

CAV suppresses the immune system and makes survivors highly susceptible to other infections. Though mortality from CAV is not especially high, later death sue to bacterial infection is economically significant. Individuals who survive Chicken Anemia Virus are at high risk of falling fatally ill by a otherwise simple bacterial infection later in life [2, 3].

This virus affects both meat and egg-type chickens, though it is more rampid among commercially produced chickens. Disease most often occurs and is most lethal during the first three weeks of life. Chickens of any age may be infected via oral and respiratory routes, but their mature immune systems are much more resistant. An individual infected with CAV will be a life-long carrier [2].

A particularly interesting aspect of Chicken Anemia Virus is it's symptom of depression. The presence of depression in non-human mammals is disputed, and hardly found in animals beyond mammals. However, CAV is consistently seen to incite behaviors indicative of depression. Lethargy, social isolation, loss of appetite, and mental dullness are the most highly reported symptoms [1, 3]. The onset of depression implies that CAV has greater effects beyond bond marrow atrophy and immunosuppression- it is a neurological infection as well.

The Chicken Anemia Virus presents the possibility of learning about avian depression. To confirm mental depression outside of the class mammalia may lead to a greater understanding of the affliction. Because of their abundance, ease of obtaining, and our comprehensive knowledge of them, common chickens would be a great model system for research regarding depression.

Genome Structure

Chicken Anemia Virus has three open reading frames (ORF), VP1, VP2 and VP3, which code for the three viral proteins. VP1 is the capsid protein of CAV. VP3 is responsible for inciting apoptosis. VP2 is a multi-purpose protein. VP2 works partially to aid VP1 in the capsid structure and strength [4].Though the exact mechanism of VP3 is unknown, it is likely that VP3 is highly attracted to chromatin, binds to it, and disturbs the tightly-coiled structure [5].

Due to it's apoptotic capabilities, VP3 may be a candidate for cancer treatment research [1].

Virion Structure of CAV

The CVA virion is a non-enveloped icosahedral structure 23-25nm in diameter.

This virus is especially hearty, as it has proven resistant to high temperature, acidic pH, chloroform, and commercial disinfectants. It can be destroyed with hypochlorite and iodophor [1].

Reproductive Cycle of CAV in a Host Cell

Viral Ecology & Pathology

The Chicken Anemia Virus is most often transmitted from mother to offspring before hatch. The infected mother will pass the virus on via the egg shell, though which CAV will penetrate.

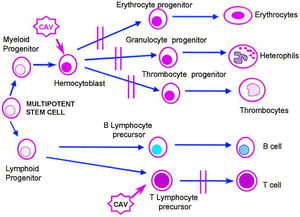

Chicken Anemia Virus is primarily effective by targeting lymphoid progenitor cells (B and T cells) in the thymus and red blood progenitor cells in the bone marrow.

Damaged erythroid cells in bone marrow results in the severe anemia so indicative with CAV. Specifically, it is the ruin and removal of hemocytoblasts in bone marrow that incites anemia. Production of red blood cells drops dramatically, resulting in anemia. A loss of thrombocytes and granulocytes also results from the damaged erythroid cells.

The depletion of lymphocytes equates to immunosuppression. With fewer B and nearly no T cells, the individual is highly susceptible to infection. This explains why CAV fatality is often directly due to an unrelated bacterial infection [5].

While the symptom of depression in chickens afflicted with Chicken Anemia Virus has been reported by many different owners, the pathology is not known. This is not suspected to be depression stemming from a chemical imbalance, and may be best described as the "chicken blues." Just as a human feels sad when he/she has been sick for a long time, chickens with CAV may be exhibiting signs of emotional sadness.

References

[1] "Chicken Anemia Virus Disease." WikiVet. MediaWiki. 17 August 2012. Web. 13 September 2012. http://en.wikivet.net/Chicken_Anaemia_Virus_Disease

[2] Rosenberger, J. K. and Cloud, S. S. "Chicken Anemia Virus." Poultry Science. 1998. 77:1190-1192.

[3] Sommer, Franz and Cardona, Carol. "Chicken Anemia Virus in Broilers: Dynamics of the Infection in Two Commercial Broiler Flocks." American Association of Avian Pathologists. 2003. 47: 1466-1473.

[4] Lacorte, C., Lohuis, H., Goldbach, R. and Prins, M. Assessing the expression of chicken anemia virus proteins in plants. 2007. Virus Research. 129: 80-86.

[5] Adair, B.M. Immunopathogenesis of Chicken Anemia virus. Developmental and Comparative Immunology. 2000. 24: 247-255.

Page authored by Ellen Gaglione for BIOL 375 Virology, September 2010