Microalgal symbionts: The coral-dinoflagellate relationship

Introduction

Many microbes form symbiotic relationships with plants and animals. These relationships are complex and often persist throughout evolutionary time as organisms evolve in tandem. Some organisms are facultative symbionts, meaning that both partners can live independently while others are obligative, meaning that one cannot survive without the other. In obligative symbionts it is common that one organism provides necessary nutrients that the other organism is incapable of manufacturing. A unique obligative symbiotic relationship occurs between corals and their microalgal symbionts.

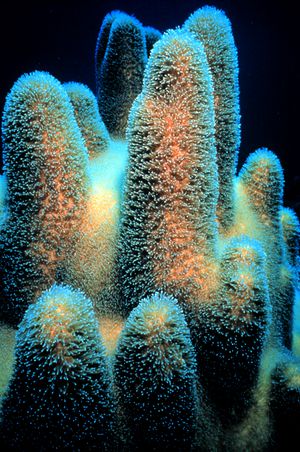

Corals are in the class Anthozoa and phylum Cnidaria. Species that live in the warm, clear waters near the equator are most well known, but species have also been found to live in deeper colder waters which are nearer to the poles. They form calcium carbonate skeletons as a result of their partnership with microalgae. The microbes in symbiotic relationships with the coral are endosymbiotic dinoflagellates. These dinoflagellates are single-celled algae in the family Symbiodiniaceae, and the most common dinoflagellates in tropical coral are of the genus Symbiodinium.1 The clear waters near the equator are nutrient poor and coral do not have the resources to produce their own energy; they rely on their photosynthetic symbionts for energy. The dinoflagellates conduct photosynthesis and instead of retaining the products of photosynthesis for their own use, release most of it into the tissue of the coral, which gives it enough energy to form calcium carbonate skeletons. As the coral metabolizes the products of photosynthesis, the waster produced is recycled to the dinoflagellates in the form of inorganic nutrients and CO2. Eventually, the coral produces a large enough skeleton to be stable and withstand waves in shallow waters. Most tropical corals exist in colonies and many colonies together form a reef.

There has been a recent surge of interest in coral reefs due to concerns of coral bleaching. As climate change continues, and the earth's temperature increases, the acidity of the oceans is also increasing. This increase in acidity is causing the calcium carbonate structures of corals and other marine organism to become compromised, affecting survival. This phenomenon has been termed "coral bleaching". Coral reefs depend on a delicate balance of conditions to thrive and coral bleaching can push reefs to the edge. The decimation of coral reefs is not only harmful because of the loss of species, but also because coral reefs occupy a unique place in tropical marine ecology. Coral reefs function as ecosystem engineers, creating habitats in an otherwise barren environment. This habitat creation is a factor in the rich communities of life seen in and around coral reefs.

Host-Symbiont Interaction

The process of microalgal recruitment to growing corals is complex and varies in different areas. In the Caribbean and Western Pacific, there tend to be a few generalist symbionts that inhabit a wide range of corals. This is due to the location of these areas in relation to other pockets of tropical reefs. Because the areas are similar and not isolated, it is easy for a only a few species of microalgal symbionts to colonize diverse corals.

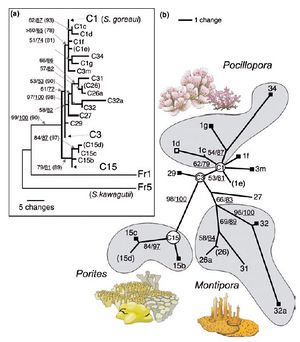

However it has been found that in other more isolated areas, there is no such generality in the range of microalgal symbionts. In Hawaii, which is very isolated, researchers have found that there is a high degree of diversity and host specificity (See Figure). The trade-off between having a wide range of available symbionts and a narrow range is also illustrated in the Hawaiian corals.2

Section 2

Include some current research in each topic, with at least one figure showing data.

Section 3

Include some current research in each topic, with at least one figure showing data.

Conclusion

Overall paper length should be 3,000 words, with at least 3 figures.

References

Weber MX and Medina M. 2012. The role of microalgal symbionts (symbiodinium) in holobiont physiology. Adv Bot Res 64:119-40.

More references coming soon!

Edited by Breanna Walker, a student of Nora Sullivan in BIOL187S (Microbial Life) in The Keck Science Department of the Claremont Colleges Spring 2013.