The Skin Microbiome and Malaria: Difference between revisions

Petriceksa (talk | contribs) |

Petriceksa (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

<br> Malaria progresses in two stages. In the first stage, the Plasmodium parasite (in sporozoite form) is injected into the host bloodstream by a mosquito vector, where sporozoites then travel to the liver <ref>[https://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/malaria/Pages/default.aspx NIAID (2016). "Malaria"]</ref>. Once inside liver cells, these sporozoites spend the next 5-16 days dividing at rapid rates into haploid merozoites. Merozoites build-up in the liver cells causes cell rupture, which then releases the merozoites back into the bloodstream. This begins the second stage of the disease, where the parasites infect red blood cells, undergo many cycles of asexual reproduction, and cause their new host cells to rupture as well, further propagating merozoite production. Infection and rupture cycles repeat every 1-3 days, which manifest themselves in the shivering and fever cycles mentioned above <ref>[https://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/malaria/Pages/default.aspx NIAID (2016). "Malaria"]</ref>. | <br> Malaria progresses in two stages. In the first stage, the Plasmodium parasite (in sporozoite form) is injected into the host bloodstream by a mosquito vector, where sporozoites then travel to the liver <ref>[https://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/malaria/Pages/default.aspx NIAID (2016). "Malaria"]</ref>. Once inside liver cells, these sporozoites spend the next 5-16 days dividing at rapid rates into haploid merozoites. Merozoites build-up in the liver cells causes cell rupture, which then releases the merozoites back into the bloodstream. This begins the second stage of the disease, where the parasites infect red blood cells, undergo many cycles of asexual reproduction, and cause their new host cells to rupture as well, further propagating merozoite production. Infection and rupture cycles repeat every 1-3 days, which manifest themselves in the shivering and fever cycles mentioned above <ref>[https://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/malaria/Pages/default.aspx NIAID (2016). "Malaria"]</ref>. | ||

<ref>[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3847443/ Bartlett et al.: Oncolytic viruses as therapeutic cancer vaccines. Molecular Cancer 2013 12:103.]</ref> | <ref>[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3847443/ Bartlett et al.: Oncolytic viruses as therapeutic cancer vaccines. Molecular Cancer 2013 12:103.]</ref> <br> | ||

<br> While the most commonly-known risk factors for malaria are geographic location, socioeconomic level, and lack of proper medical care, research suggests that an individual’s skin microbiome can heavily influence attractiveness to malaria-carrying mosquitoes <ref>[http://cabdirect.org/abstracts/20113162376.html;jsessionid=D3C4DB995951FD6E40D02C43073642EE Carde, H & Gibson, G (2016). "Host finding by female mosquitoes: mechanisms of orientation to host odours and other cues."]</ref>. Odorous chemical cues are key to mosquito orientation and landing during host location, and skin flora play a large role in the process by affecting human odor production. Specifically, these microbes metabolize lipids and other compounds in naturally odorless sweat, producing volatile odor compounds attractive to anthropophilic mosquitoes (Olanga et al, 2010). Skin bacteria vary widely in their metabolic pathways, and thus have differing volatile odor productions. As such, composition of skin flora can have large effects on host location in such mosquitoes. | |||

<br><br>A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes. | <br><br>A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes. | ||

Revision as of 14:08, 25 April 2016

Introduction

By Aldis Petriceks

Double brackets: [[

Closed double brackets: ]]

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

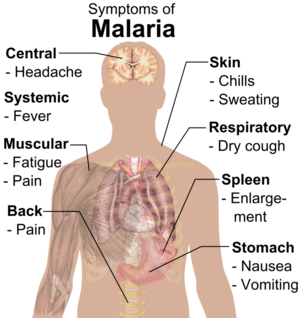

Malaria is a deadly disease caused by the protozoan Plasmodium, and spread through mosquito bites. [1] The most common ailments are fever, chills, and flu-like symptoms which typically begin within a month of infection [2]. Other symptoms include headache, vomiting, jaundice, shivering, and joint pain. The most notable sign of a malaria infection is paroxysm – which includes cycles of cold and shivering followed by fever and sweating. While immediate treatment can typically facilitate a full recovery, those without access to medical care can fall fatal to the disease within days. There are currently 3.4 billion people living in high-risk areas, which led to 500,000 deaths from malaria in 2013 alone (CDC). The majority of these deaths occur in underdeveloped tropical and sub-tropical countries, which in turn incur the bulk of the $12 billion USD yearly cost associated with fighting the disease.

Malaria progresses in two stages. In the first stage, the Plasmodium parasite (in sporozoite form) is injected into the host bloodstream by a mosquito vector, where sporozoites then travel to the liver [3]. Once inside liver cells, these sporozoites spend the next 5-16 days dividing at rapid rates into haploid merozoites. Merozoites build-up in the liver cells causes cell rupture, which then releases the merozoites back into the bloodstream. This begins the second stage of the disease, where the parasites infect red blood cells, undergo many cycles of asexual reproduction, and cause their new host cells to rupture as well, further propagating merozoite production. Infection and rupture cycles repeat every 1-3 days, which manifest themselves in the shivering and fever cycles mentioned above [4].

[5]

While the most commonly-known risk factors for malaria are geographic location, socioeconomic level, and lack of proper medical care, research suggests that an individual’s skin microbiome can heavily influence attractiveness to malaria-carrying mosquitoes [6]. Odorous chemical cues are key to mosquito orientation and landing during host location, and skin flora play a large role in the process by affecting human odor production. Specifically, these microbes metabolize lipids and other compounds in naturally odorless sweat, producing volatile odor compounds attractive to anthropophilic mosquitoes (Olanga et al, 2010). Skin bacteria vary widely in their metabolic pathways, and thus have differing volatile odor productions. As such, composition of skin flora can have large effects on host location in such mosquitoes.

A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes.

Section 1

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Every point of information REQUIRES CITATION using the citation tool shown above.

Section 2

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Mosquito-Attracting Skin Bacteria

Section 4

Conclusion

References

- ↑ CDC, (2016). "Malaria"

- ↑ Caraballo, H (2014). "Malaria, Dengue, and West Nile Virus"

- ↑ NIAID (2016). "Malaria"

- ↑ NIAID (2016). "Malaria"

- ↑ Bartlett et al.: Oncolytic viruses as therapeutic cancer vaccines. Molecular Cancer 2013 12:103.

- ↑ Carde, H & Gibson, G (2016). "Host finding by female mosquitoes: mechanisms of orientation to host odours and other cues."

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2016, Kenyon College.