The Temperature Relationship of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis: Difference between revisions

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

<br><b>Species:</b> <i>B. dendrobatidis</i> | <br><b>Species:</b> <i>B. dendrobatidis</i> | ||

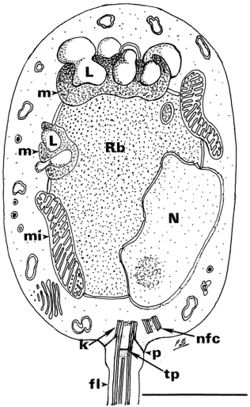

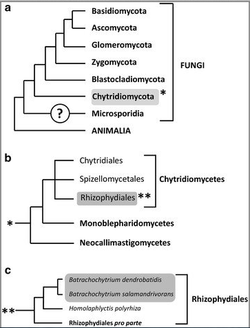

<br>After its discovery, the amphibian chytrid fungus was placed in a new genus, <i>Batrachochytrium</i>, which was originally in the order Chytridiales<ref name=Longcore1999>[https://www.jstor.org/stable/3761366?seq=1/ Longcore et al. 1999. Batrachochytrium Dendrobatidis gen. et sp. nov., a Chytrid Pathogenic to Amphibians. Mycologia. 91:219-227]</ref>. The designation of the fungus was initially determined by examining the zoospore ultrastructure<ref name=Berger2005/>. However the discovery of new ultrastructural and molecular characteristics helped to segregate different orders, designating <i>Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis</i> as a member of the order Rhizophydiales<ref name=MargulisChapman2009>[https://books.google.com/books?id=9IWaqAOGyt4C&pg=PA221&lpg=PA221&dq=Rhizophydiales+or+Chytridiales&source=bl&ots=1FA01hOf7B&sig=ACfU3U35iRTDCj6K4rWojQRwoh3Z77wn7A&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiCjOC0r43pAhUDrJ4KHT8_DQsQ6AEwEXoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=Rhizophydiales%20or%20Chytridiales&f=false/ Margulis and Chapman. 2009. Chytridiomycota. In: Kingdoms and Domains: An Illustrated Guide to the Phyla of Life on Earth. Academic Press, Cambridge, pp.220-221.</ref>. This separation was supported by analysis of the small subunit ribosomal DNA (ssu-rDNA) sequence of the pathogen. At the time of its designation, <i>Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis</i> was the only known member of its genus<ref name=Longcore1999/>. It was also the only known member of Chytridiomycota to parasitize vertebrates<ref name=Rosenblum2010/>, and is one of a very limited number of endobiotic fungi in the order Rhizophydiales<ref name=Greenspan2012>[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22968788/ Greenspan et al. 2012. Host invasion by <i>Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis:</i> fungal and epidermal ultrastructure in model anurans. Dis Aquat Org. 100:201-210]</ref>. | |||

<br>It was not until 2013 that another member of the Batrachochytrium genus became known. A second pathogenic species, <i>Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans</i> (<i>Bsal</i>) was discovered<ref name=FisherGarner2020/>. Similarly to <i>B. dendrobatidis</i>, <i>B. salamandrivorans</i> causes chytridiomycosis and death in its host, however in this case the species preferentially infects salamanders<ref name=Muletz2014>[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4118919/ Muletz et al. 2014. Unexpected Rarity of the Pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in Appalachian Plethodon Salamanders: 1957–2011. PLOS. 9:e103728]</ref>. | |||

==Effect on Amphibians== | ==Effect on Amphibians== | ||

Revision as of 01:18, 3 May 2020

Introduction

By [Eva Brazer]

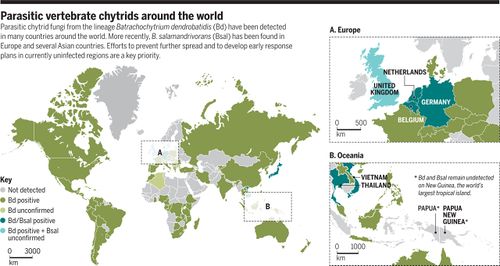

Amphibian species around the world are experiencing unprecedented population decline due to the emerging infectious disease chytridiomycosis, which is caused by the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd)[2]. The chytrid pathogen is considered an emerging infectious disease because it was discovered and described only in the last twenty years[3], and has continued to spread globally causing devastating effects[4]. Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis has been identified on every continent on which amphibians are present[2].

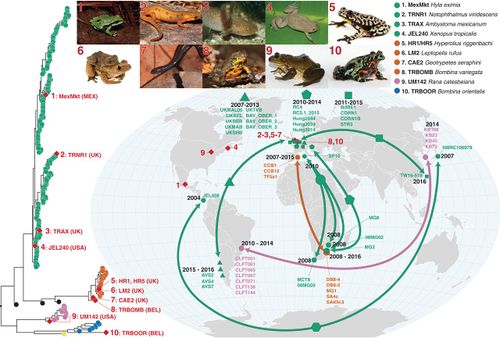

Recent global mapping initiatives reported that Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis had been identified as having infected 1,015 of the 1,854 species examined (54%). Further population analysis found that the fungus has resulted in the decline of at least 501 species (6.5% of all amphibian species), with 124 experiencing a decrease in the species population of over 90%[5]. Over a hundred presumed extinctions have been attributed to chytridiomycosis[6]. The catastrophic impact of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis is so significant that it is believed to be the largest threat to the biodiversity of any class of vertebrate[2]. Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis has been documented in hundreds of amphibian species, and reports of infection in new species and geographic locations are continually increasing[6].

Climate change models are predicting an increase in the frequency and magnitude of temperature fluctuations[7]. This has caused concern that these temperature fluctuations may lead to increased pathogen development, transmission, and ectotherm-host susceptibility[8]. The parasitic performance of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis is sensitive to temperature[8]. By examining the relationship between pathogen and host interactions particularly in relation to temperature fluctuations, scientists can better predict and mitigate the spread of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis to new amphibian populations.

Phylogeny

Scientific classification

Kingdom: Fungi

Division: Chytridiomycota

Class: Chytridiomycetes

Order: Rhizophydiales

Genus: Batrachochytrium

Species: B. dendrobatidis

After its discovery, the amphibian chytrid fungus was placed in a new genus, Batrachochytrium, which was originally in the order Chytridiales[10]. The designation of the fungus was initially determined by examining the zoospore ultrastructure[1]. However the discovery of new ultrastructural and molecular characteristics helped to segregate different orders, designating Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis as a member of the order Rhizophydiales[11]. This separation was supported by analysis of the small subunit ribosomal DNA (ssu-rDNA) sequence of the pathogen. At the time of its designation, Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis was the only known member of its genus[10]. It was also the only known member of Chytridiomycota to parasitize vertebrates[6], and is one of a very limited number of endobiotic fungi in the order Rhizophydiales[12].

It was not until 2013 that another member of the Batrachochytrium genus became known. A second pathogenic species, Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal) was discovered[5]. Similarly to B. dendrobatidis, B. salamandrivorans causes chytridiomycosis and death in its host, however in this case the species preferentially infects salamanders[13].

Effect on Amphibians

Effect of Temperature

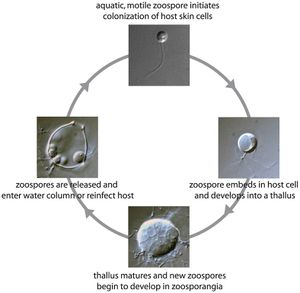

Life Cycle

Effect of Temperature

Geographic Distribution

Effect of Temperature

Climate Change

Conclusion

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Berger et al. 2005. Life cycle stages of the amphibian chytrid Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Inter-Research. 68:52-63

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Weldon et al. 2004. Origin of the Amphibian Chytrid Fungus. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10(12):2100-2105

- ↑ Berger et al. 1998. Chytridiomycosis causes amphibian mortality associated with population declines in the rain forests of Australia and Central America. PNAS. 95:9031-9036

- ↑ Piotrowski et al. 2004. Physiology of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, a Chytrid Pathogen of Amphibians. Mycologia. 96:9-15

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Fisher, M.C., T.W.J. Garner. 2020. Chytrid fungi and global amphibian declines. Nature Reviews Microbiology. (1740-1526).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Rosenblum et al. 2010. The Deadly Chytrid Fungus: A Story of an Emerging Pathogen. PLoS Pathogens. 6(1):e1000550

- ↑ Bradley et al. 2019. Shifts in temperature influence how Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis infects amphibian larvae. Health and Medicine. 14:(9)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Stevenson et al. 2013. Variation in Thermal Performance of a Widespread Pathogen, the Amphibian Chytrid Fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. PLoS ONE. 8(9):e73830

- ↑ Rooij et al. 2015. Amphibian chytridiomycosis: A review with focus on fungus-host interactions. Veterinary Research. 46(1):137.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Longcore et al. 1999. Batrachochytrium Dendrobatidis gen. et sp. nov., a Chytrid Pathogenic to Amphibians. Mycologia. 91:219-227

- ↑ [https://books.google.com/books?id=9IWaqAOGyt4C&pg=PA221&lpg=PA221&dq=Rhizophydiales+or+Chytridiales&source=bl&ots=1FA01hOf7B&sig=ACfU3U35iRTDCj6K4rWojQRwoh3Z77wn7A&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiCjOC0r43pAhUDrJ4KHT8_DQsQ6AEwEXoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=Rhizophydiales%20or%20Chytridiales&f=false/ Margulis and Chapman. 2009. Chytridiomycota. In: Kingdoms and Domains: An Illustrated Guide to the Phyla of Life on Earth. Academic Press, Cambridge, pp.220-221.

- ↑ Greenspan et al. 2012. Host invasion by Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis: fungal and epidermal ultrastructure in model anurans. Dis Aquat Org. 100:201-210

- ↑ Muletz et al. 2014. Unexpected Rarity of the Pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis in Appalachian Plethodon Salamanders: 1957–2011. PLOS. 9:e103728

- ↑ Bower et al. 2017. Amphibians on the brink: Preemptive policies can protect amphibians from devastating fungal diseases. Science. 357:454-455

- ↑ O’Hanlon et al. 2018. Recent Asian origin of chytrid fungi causing global amphibian declines. Science. 360:621-627

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2018, Kenyon College.