Transmission of T. Forsythia to humans from a dog bite

Introduction

T. forsythia is an infectious microbe that is found in the oral cavities of mammals. It is an infectious agent associated with the periodontal diseases of gingivitis and periodontal disease. Gingivitis is characterized by tissue inflammation, and periodontitis is characterized by alveolar bone resorption and bone loss. These diseases/infections become present when plaque buildup is great and allow T. forsythia to have a place to live and reproduce. In the case of dogs, it is common for them to have problems with periodontal diseases due to the fact that they cannot brush their teeth. This poses a problem to humans that are bitten by canines with plaque buildup because they run the risk of being exposed to this microbe. []

Tannerella forsythia

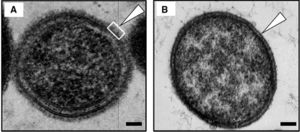

T. Forsythia is a bacterium found within the mouths of mammals and primates. It is mostly found in the oral cavities of humans, dogs, cats, and monkeys. When a gram stain is applied, it is known to be Gram-negative and survives under anaerobic conditions. T. Forsythia only appears in culture from the mouths of mammals with periodontal diseases. These diseases include gingivitis, which is characterized by tissue inflammation, and periodontitis, which is characterized by alveolar bone resorption and bone loss. This bacterium is labeled under the species Bacteroidetes, which led to its original name, Bacteroides forsythia. It has a short, rod-shaped body, and its lack of a flagellum or pili make it non-motile. This lack of mobility or any sort of attachment appendage causes it to be reliant on a biofilm in the form of plaque for it to attach to the surface of teeth or other periodontal tissues. They also have an S-layer comprised of glycoprotein that protects both the inner and outer membranes of the cell. []

Red Complex

T. Forsythia is a part of a group of microbes known as the “Red Complex.” This group of bacteria consists of T. Forsythia, Treponema denticola, and Porphyromonas gingivalis. All of these bacteria are typically found in the oral cavities of mammals. They all are the cause of periodontal diseases such as periodontitis and gingivitis. One of the symptoms and initial clues that these bacteria are present in the periodontal tissues is swelling, inflammation, and bleeding when probed this is where the name Red Complex comes from. Red complex bacteria grow and live as surface attached biofilm plaque in the subgingival area surrounding and underneath the teeth (Homma). T. forsythia, other red complex bacteria and their byproducts are recognized by the host’s immune system and leads to the secretion of cytokines that recruit phagocytic cells such as neutrophils and macrophages. Recognition of any of these bacteria causes a release of antimicrobial peptides for bacterial killing (Homma). In response, the body produces uncontrolled inflammation that results in tissue destruction and increased periodontal pocket depth (Homma). The red, inflamed tissue that results is how the red complex gets its namesake. There is also the possibility for the destruction of tooth-supporting tissue and bone/tooth loss. If any of these symptoms are present in your dog, it is recommended that you take them to them a veterinarian because any members of the Red Complex are easily transmittable from organism to organism. []

Culture

T. Forsythia is a difficult microbe to culture because it is anaerobic. Since they require environments without Oxygen, these cultures are difficult and expensive to create. It is relatively slow growing and requires fastidious growth conditions. When cultured from bite wounds inflicted by dogs, T. Forsythia was shown to grow best in N-Acetylmuramic acid deficient conditions. N-Acetlymuramic acid is an ether of lactic acid and N-Acetylglucosamine, and is often found in the peptidoglycan of bacterial cell walls. However, when T. Forsythia was cultured from human mouths, it was found that they did not grow under conditions with N-Acetylmuramic acid present. In culture, the colonies are very small and are opaque colored. T. Forsythia has also been know to be able to metabolize a range of substrates and like other enteric Bacteroides species, hydrolyzes aesculin. []

Periodontal Diseases in Canines

These infections are some of the most commons in dogs as well as cats today. They first start to form when food buildup occurs on a dog’s teeth, and is not properly wiped away. This buildup then transforms into plaque and accumulates along the dog’s gum line. Plaque can then transform into calculus when combined with saliva and other minerals that are common in a dog’s mouth. Calculus is the hardening of plaque, and because this occurs along the gum line, causes gun irritation and inflammation. Theses buildups are breeding grounds for bacteria that live in oral cavities. Microbes from the Bacteroidetes, Actinomyces, and the Streptococcus families all enjoy these kinds of conditions and have been found in cultures from canine tooth plaque. These symptoms are triggers for gingivitis and periodontal disease. In extreme cases, the calculus will build up under the gum and cause separation between the gum and the tooth. This leads to bone degeneration, tooth loss, and pus formation, and the canine will officially have an irreversible periodontal disease. In diagnosing periodontal diseases, a veterinarian will probe the infected area of the dog’s mouth, and if more than two millimeters of space are found between the tooth and gum of the affected area, then the canine officially has a periodontal disease. Certain canine breeds are more likely to be affected then others. The toy breeds are born with crowded teeth, which make it more likely that they will struggle with plaque buildup. Dogs that groom themselves also run a greater chance of getting an infection due to the nature of some areas of the body they have to clean. Poor nutrition can also be a problem because the dog may not be receiving enough nutrients to ward off disease, or they may be receiving those that are helping plaque to harden. The best way to prevent your dog from receiving a periodontal infection is to brush their teeth regularly and wipe their mouths after they eat to remove any food buildup. (PetMD) []

Abscesses

Normally found in oral cavities, bacteria such as T. forsythia have been cultured in other locations on the human body. They are found in abscesses that form from a cut or puncture wound caused by an infected tooth. If a dog bites a person, and has plaque buildup, then there is the potential for it to spread any oral microbes that dog may be playing host to. Quite often, members of the Red Complex are detected in and are the cause of what are known as acute periradicular abscesses.

Abscesses are an accumulation of exudate (fluid emitted through a wound) consisting of bacteria, bacterial by-products, inflammatory cells, lysed inflammatory cells, and the content of those cells (Ozebek, et. al, 2010). When these bacteria enter the surrounding epithelial cells, the immune system is unable to suppress the invasion. Symptoms include redness, swelling, warmth and pus being emitted from the area, and pain. In abscesses, knowing the specific microbe that has caused the infection is important to treating it. Knowing what the microbe is and where it came from is key in prescribing the proper antibiotic. T. forsythia has been known to be most susceptible to the following antibiotics: amoxicillin, clavulanate, ampicillin, doxycycline, tetracycline, and clindamycin (Tanner & Izard, 2006), with amoxicillin and clavulanate being the most effective.

References

"PetMD." Dog Gum Disease. PetMD, n.d. Web. 21 Apr. 2016.

[Lee SW, Sabet M, Um HS, Yang J, Kim HC & Zhu W (2006) Identification and characterization of the genes encoding a unique surface (S-) layer of Tannerella forsythia. Gene 371:102–111.]

[Sharma A, Inagaki S, Honma K, Sfintescu C, Baker PJ & Evans RT (2005a) Tannerella forsythia-induced alveolar bone loss in mice involves leucine-rich-repeat BspA protein. J Dent Res 84:462–467.]

[Sharma A, Inagaki S, Sigurdson W & Kuramitsu HK (2005b) Synergy between Tannerella forsythia and Fusobacterium nucleatum in biofilm formation. Oral Microbiol Immunol 20:39–42. Sharma A, S]

At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki.

The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: PHIL_1181_lores.jpg

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Electron micrograph of the Ebola Zaire virus. This was the first photo ever taken of the virus, on 10/13/1976. By Dr. F.A. Murphy, now at U.C. Davis, then at the CDC.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Introduce the topic of your paper. What is your research question? What experiments have addressed your question? Applications for medicine and/or environment?

Sample citations: [1]

[2]

A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes.