Transmission of T. Forsythia to humans from a dog bite

Introduction

T. forsythia is an infectious microbe found in the oral cavities of mammals. It is an infectious bacteria associated with the periodontal diseases of gingivitis and periodontal disease. Gingivitis is characterized by tissue inflammation, while periodontitis is characterized by alveolar bone resorption as well as bone and tooth loss. The symptoms of these diseases give T. forsythia and other periodontal disease causing bacteria their namesake. These diseases/infections become present when plaque buildup is great and allow T. forsythia to have a place to live and reproduce. In the case of dogs, it is common for them to have problems with periodontal diseases due to the fact that they cannot brush their teeth. This poses a problem to humans that are bitten by canines with plaque buildup. If this happens, they run the risk of being exposed to this microbe, and have the potential to get an infection of the epidermis in the form of an abscess. []

Tannerella forsythia

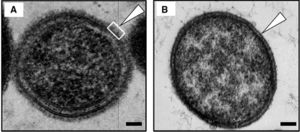

T. Forsythia is a bacterium found within the mouths and along the gum lines of mammals and primates. More specifically, it is most commonly found in the oral cavities of humans, dogs, cats, and monkeys. When a gram stain is applied, it is known to be Gram-negative and survives under anaerobic conditions. T. Forsythia only appears in culture from the mouths of mammals with periodontal diseases as well as in abscesses on humans caused from puncture wounds of infected teeth (caused by humans as well as dogs). This bacterium is labeled under the species Bacteroidetes, which led to its original name, Bacteroides forsythia. When T. Forsythia was initially discovered, researchers had a difficult time classifying it taxonomically. The microbe did not resemble any previously discovered species of oral or enteric gram-negative, anaerobic rods, particularly because of its cell morphology and slow and fastidious growth requirements (Tanner and Izard 2006). This microbe has a short, rod-shaped body with tapered ends, and its lack of a flagellum or pili makes it non-motile. This lack of mobility or any sort of attachment appendage causes it to be reliant on a biofilm in the form of plaque for it to attach to the surface of teeth or other periodontal tissues. These biofilms play an important role in T. forsythia virulence factors and are the ultimate cause of periodontal diseases in mammals. They also have an S-layer comprised of glycoprotein that protects both the inner and outer membranes of the cell. This Suface/S-Layer comprised of cell surface glycoproteins plays a role in the microbe’s attachment and integration into the oral cavity (Lee et al. 2006). Interestingly, T. forsythia and the biofilms they comprise are resistant to bile. They possess the ability to hydrolyze the components of bile, which is important for a microbe that lives in the oral cavities and have the potential to be exposed to these extreme pH conditions. []

Culture

T. Forsythia is a difficult microbe to culture because it is anaerobic. Since they require environments without Oxygen, these cultures are difficult and expensive to create. It is a relatively slow growing bacterium and requires fastidious growth conditions. If researchers can create these conditions, the fact that these microbes are anaerobic poses problems when attempting to perform PCR amplification for further studies. T. Forsythia is also known to be able to metabolize a range of substrates, and like other enteric Bacteroidetes species, hydrolyzes aesculin, a major component in bile salts. T. forsythia’s ability to break down aesculin when present, allows it to be bile-resistant. This is a major factor in it being able to build a biofilm on the periodontal tissues. In culture, the colonies of this microbe are very small and are opaque colored. They also do not grow on normal agar plates or in planktonic culture.

Dahle´n et al. (2011) discovered that from dog bites, bacteria from the Bacteroidetes species could be cultured. When cultured from bite wounds inflicted by dogs, the only growth conditions that stimulated T. Forsythia was the bacterial cell wall component, N-Acetlymuramic acid. N-Acetylmuramic acid (NAM) is an ether of lactic acid and N-Acetylglucosamine, and can often be found in the peptidoglycan of bacterial cell walls. It is not known why this specific compound is important to T. Forsythia growth in vivo. This is especially interesting because when observed in vitro, the only other source of NAM comes from other autolyzed oral bacteria (Roy et al. 2010).

Roy et al. (2010) examined the influence of sialic acid on the stimulation of T. forsythia biofilm growth. On a natural biofilm growth medium, varying amounts of sialic acid were used instead of NAM under the preferred (anaerobic) conditions of T. forsythia. The results showed that sialic acid alone does stimulate the growth of this infectious microbe. However, when sialic acid and NAM are combined as a medium, colonies could grow, but were smaller and not as prevalent (Roy et al. 2010).

[]

Periodontal Diseases in Canines

[]

S-layer and BspA

Abscesses

References

"PetMD." Dog Gum Disease. PetMD, n.d. Web. 21 Apr. 2016.

[Lee SW, Sabet M, Um HS, Yang J, Kim HC & Zhu W (2006) Identification and characterization of the genes encoding a unique surface (S-) layer of Tannerella forsythia. Gene 371:102–111.]

[Sharma A, Inagaki S, Honma K, Sfintescu C, Baker PJ & Evans RT (2005a) Tannerella forsythia-induced alveolar bone loss in mice involves leucine-rich-repeat BspA protein. J Dent Res 84:462–467.]

[Angata, T. & Varki, A. (2002). Chemical diversity in the sialic acids and related a-keto acids: an evolutionary perspective. Chem Rev 102, 439–470.]

[Varki, A. (1997). Sialic acids as ligands in recognition phenomena. FASEB J 11, 248–255.]

[Inagaki, S., Onishi, S., Kuramitsu, H. K. & Sharma, A. (2006). Porphyromonas gingivalis vesicles enhance attachment, and the leucine-rich repeat BspA protein is required for invasion of epithelial cells by ‘‘Tannerella forsythia’’. Infect Immun 74, 5023–5028.]

[Sharma A, Inagaki S, Sigurdson W & Kuramitsu HK (2005b) Synergy between Tannerella forsythia and Fusobacterium nucleatum in biofilm formation. Oral Microbiol Immunol 20:39–42. Sharma A, S]

At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki.

The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: PHIL_1181_lores.jpg

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Electron micrograph of the Ebola Zaire virus. This was the first photo ever taken of the virus, on 10/13/1976. By Dr. F.A. Murphy, now at U.C. Davis, then at the CDC.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Introduce the topic of your paper. What is your research question? What experiments have addressed your question? Applications for medicine and/or environment?

Sample citations: [1]

[2]

A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes.