Vagina: Difference between revisions

| Line 115: | Line 115: | ||

(5)[http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/topics/bacterialVaginosis/: ''Bacterial Vaginosis''] | (5)[http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/topics/bacterialVaginosis/: ''Bacterial Vaginosis''] | ||

(6) Aroutcheva, Alla A, Simoes, Jose A., and Faro Sebastian. 2001 Antimicrobial protein produced by vaginal ''[[Lactobacillus acidophilus]]'' that inhibits Gardnerella vaginalis | (6) Aroutcheva, Alla A, Simoes, Jose A., and Faro Sebastian. 2001 Antimicrobial protein produced by vaginal ''[[Lactobacillus acidophilus]]'' that inhibits ''[[Gardnerella vaginalis]]'' | ||

(7) Streptococcal infections : clinical aspects, microbiology, and molecular pathogenesis / edited by De New York : Oxford University Press, 2000. P. 223-230, 183-186. | (7) Streptococcal infections : clinical aspects, microbiology, and molecular pathogenesis / edited by De New York : Oxford University Press, 2000. P. 223-230, 183-186. | ||

Revision as of 01:34, 27 August 2008

Description of Niche

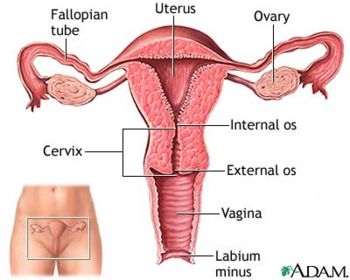

The vagina is located directly anterior to the anus and below the urethral opening. It is a muscular passageway which connects the uterus to the exterior genitals. Immediately outside the vaginal opening is the labia minora, which is also known as the inner lips, which then leads into the labia majora, the outer lips. Typically after puberty, the labia majora is covered with hair, otherwise known as mons pubis. All together, the labia minora, labia majora, clitoris, mons pubis, and vestibule is called the vulva. Neighboring parts surrounding the vagina also include the clitoris, urethral orifice, vestibule, and hymen. The clitoris is a hard round organ directly on top of the vulva and encircles and extends into the vagina. This organ is to supply pleasure during sexual intercourse and is at the anterior end joining the labia minora. The urethral orifice lies above the vagina and below the clitoris and functions to excrete urine stored in the urinary bladder. The hymen is a membrane which acts like a flap partially covering the opening of the vagina.

Physical Conditions

With an approximate pH value ranging from 3.8 to 4.5, the vagina functions in a relatively acidic environment. This pH range is required for a healthy vagina for protection purposes. Any pH value higher than 4.5 potentially leads to serious problems. The vagina is typically at or slightly above normal body temperature. This acidic environment is important to maintain so that certain pathogens can not cultivate in that area. But usually this is not an issue because the acidic environment makes it impossible for the pathogens to survive. It is important for moisture maintenance to prevent dryness and irritation. To the left and right of the vaginal opening are two oval shaped vestibular glands, otherwise known as Bartholon glands, which secrete mucous for lubrication purposes. During sexual arousal, these glands also secrete addition lubricants to prevent pain during intercourse. Throughout a woman’s life, there are fluctuations in the amount of estrogen produced in the body. Estrogen assures that the tissues surrounding the vagina retains elasticity and retains moisture. However, when a woman experiences menopause, estrogen levels decreases dramatically which ultimately leads to vaginal dryness, irritation, and decrease in tissue elasticity.

Influence by Adjacent Communities

Is your niche close to another niche or influenced by another community of organisms?

!!!currently being worked on by Jason!!!!

Conditions under which the environment changes

Do any of the physical conditions change? Are there chemicals, other organisms, nutrients, etc. that might change the community of your niche.

A mathematical model for kefiran production by Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens was established, in which the effects of pH, substrate and product on cell growth, exopolysaccharide formation and substrate assimilation were considered. The model gave a good representation both of the formation of exopolysaccharides (which are not only attached to cells but also released into the medium) and of the time courses of the production of galactose and glucose in the medium (which are produced and consumed by the cells). Since pH and both lactose and lactic acid concentrations differently affected production and growth activity, the model included the effects of pH and the concentrations of lactose and lactic acid. Based on the mathematical model, an optimal pH profile for the maximum production of kefiran in batch culture was obtained. In this study, a simplified optimization method was developed, in which the optimal pH profile was determined at a particular final fermentation time. This was based on the principle that, at a certain time, switching from the maximum specific growth rate to the critical one (which yields the maximum specific production rate) results in maximum production. Maximum kefiran production was obtained, which was 20% higher than that obtained in the constant-pH control fermentation. A genetic algorithm (GA) was also applied to obtain the optimal pH profile; and it was found that practically the same solution was obtained using the GA.

Microbes Present

Lactobacillus is one of the main microorganisms responsible for maintaining a healthy vaginal flora. Its production of Lactic acid contribute to the vaginal acidic environment. There are different strains of Lactobacillus able to colonize the vaginal flora, however, those with maximal adherence to the epithelium such as Lactobacillus acidophilus help against bacterial vaginosis (BV) due to their hydrogen peroxide producing capabilities. Bacterial Vaginosis is caused when there is a lack of Lactobacillus in the vaginal flora, allowing various types of microbes to inhabit the environment leading to complications such as pelvic inflammatory disease and sexually transmitted diseases like HIV.

Current research is identifying the best strain of Lactobacillus in order to recolonize a healthy vaginal flora. McLean and Rosenstein studied several Lactobacillus strain in order to identify the best strain able to re-colonize the vaginal flora of women with BV. This strain should be able to produce sufficient H2O2, be able to inhibitory activity against BV bacteria, acid production, and have strong adherence ability to the vaginal epithelial cell (VEC). They found two strains of the L. acidophilus (61701 and 48101) to have such characteristics (2).

Sha et al. show a correlation between Lactobacillus and BV, however, an inverse correlation with HIV (1). Furthermore, BV bacteria have been shown to upregulate HIV expression. Therefore, by suntanning a healthy vaginal flora by preventing BV infections, Lactobacillus acidophilus can help combat sexually transmitted diseases. Also, LactobacillusHydrogen Peroxide has been shown to have virucidal effects allowing the vaginal flora to have some protection against pathogens (2).

Gardnerella Vaginalis is one of the microorganisms that causes an infection of the vagina known as bacterial vaginosis. The infection is thought to be transmitted through sexual activity, but can also be found in women with no cases of sexually transmitted diseases. Douching and using intrauterine devices (IUDs) can also help lead to the cause of BV. When infected, the vagina secrets a gray or yellow discharge, which is often accompanied with a “fishy” smell. (4) Gardnerella vaginalis, along with other bacteria, inhabit the vagina and cause a chemical imbalance. These bacteria outnumber the amount of Lactobacillus found in the vagina, which are beneficial and essential to the vagina. (5)

Current research has shown that a type of Lactobacillus, Lactobacillus acidophilus, inhibits the growth of the bacteria Gardnerella Vaginalis. Aroutcheva, Simoes, and Faro performed experiments using two different methods in order to determine the effect of L. acidophilus on G. Vaginalis. Lactobacillus is an important microbe essential to keeping a healthy vaginal environment. Microbes such as G. Vaginalis, are detrimental to the vaginal environment and could cause infections such as bacterial vaginosis. L. acidophilus 160 was isolated from a healthy vaginal microflora, purified, and was then used differently in each experiment. One method required the inoculation of the L. acidophilus into defined media, and the other required the growth of the strain in MRS agar. The defined media method showed that the growth of G. Vaginalis was inhibited by substances found in the media in which the L. acidophilus was added to. The agar method showed that the growth of G. Vaginalis was inhibited by the bacteriocin, a protein produced by bacteria, that was released from the L. acidophilus 160 strain. (6)

Group B Beta Streptococcus (S. agalacitae)

S. agalactiae is a gram-positive, beta-hemolytic, opportunistic pathogenic coccus which colonizes the vaginal and gastrointestinal/rectal tract of healthy adults by adherence to surfaces of vaginal epithelial cells. The distal vagina is more frequently colonized than rectal sites in both pregnant and non-pregnant adults. The polysaccharide antiphagocytic capsule is the most prominent virulence factor as it binds maximally onto vaginal epithelial cells in the acidic pH levels of vaginal mucosa where attachment does not depend on capsular serotype or bacterial viability. [9] S. agalactiae is acquired by infants born to colonized mothers via vertical transmission in 29-72% of cases by a process involving the bacterium undergoing adherence to vaginal epithelial cells and resistance to mucosal immune defenses such as immunoglobulin A (IgA).[7] Once thought to be pathogens of domestic animals, S. agalactiae is the leading cause of neonatal sepsis in humans resulting in early-onset infections of pneumonia, septicemia and late-onset infections of meningitis or bacteremia.

S. agalactiae has a evolutionary relationship between the bacterium and the host [7]. There exists selective pressures for S. agalactiae interaction with host to establish colonization and ensure transmission to newly susceptible hosts(neonates). Host factors play a significant role in determining the pathogenic potentials of S. agalactiae.

Other non-microbes present

Fungi:

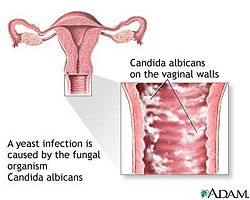

Fungi are eukaryotic organisms and their DNA is enclosed in a nucleus. Fungi are said to be "plant like", but fungi do not make their own food from sunlight like plants do. Fungi are very useful to humans as they have helped make antibiotics to fight bacterial infections. but can also be deadly that cause diseases and infections. Fungi come in a variety of shapes, sizes, and different types. They can range from enormous chains of cells that can stretch for miles or single individual cells. An example of a fungal infection to the vagina would be a Fungal Yeast Infection.

Bacteria:

Bacteria consist of only a single cell but are amazingly complex. Bacteria have also been found that can live in temperatures above boiling point and well below freezing temperatures. They "eat" everything from sugar and starch to sunlight, sulfur, and iron. Bacteria have fallen into a category of life known as the Prokaryotes. Moreover, Prokaryotes' genetic material, or DNA, is not enclosed in a cellular compartment called the nucleus. Bacteria along with their microbial cousins the archaea were the earliest forms of life on Earth. They have played a vital role in shaping our planet into one that could support the larger forms of life through the process of photosynthesis. A great example of bacteria in the vagina is Bacterial vaginitis which results in a vaginal discharge. Bacterial vaginitis is caused by bacteria and treatment is usually with antibiotics.

Viruses:

A virus is a small bundle of genetic material (DNA or RNA) that is carried in a shell called the viral coat, or capsid, which is made up of bits of protein called capsomeres. However, viruses cannot metabolize nutrients, produce and excrete wastes, move around their own, or even reproduce unless they are inside another organism's cells. Ultimately, viruses are not even cells yet they have played key roles in shaping the history of life on our planet by shuffling and redistributing genes in and among organisms and by causing diseases in animals and plants. A perfect example of viruses in the vagina is Viral vaginitis that can be caused by herpes simplex virus that is spread by sexual intercourse.

Microbe Interaction

Lactobacillus not only helps maintain the acidic environment in the vagina, but also helps prevent infections by competing with pathogenic microbes such as G. Vaginalisis. Two different ways Lactobacillus helps combat pathogenic microbes is through receptor binding interference and self-aggregation (13). Researchers at the Universidad de Oviedo, Spain postulated that L. acidophilus and G. vaginalis possibly bind the the same receptor molecule with L. acidophilus having a higher affinity, therefore, displacing G. vaginalis. Furthermore, Lactobacillus self aggregation in the presence of pathogenic microbes helps prevent the microbe from attaching to receptors.

Current research shows inhibition of uropathogenic microbes, specifically S. Agalactiae and G. vaginalis, by vaginal epithelial cell adherence of three strains of human vaginal lactobacilli ( L. acidophilus, L. gasseri, and L. jensenii) in vitro via receptor competition and co-aggregation. [13] Vaginal epithelial cells have glycolipid receptors which are targeted by both S. Agalactiae and lactobacillus. Lactobacilli inhibits the opportunistic pathogen S. Agalactiae by competing for receptors present on surfaces of vaginal epithelial cells and also by co-aggregating with uropathogenic bacteria to inhibit growth when antimicrobial compounds, such as lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide, are produced [13].

Microbes environment change

Do they alter pH, attach to surfaces, secrete anything, etc. etc.

Metabolism that affects their environment

Do they ferment sugars to produce acid, break down large molecules, fix nitrogen, etc. etc.

Current Research

Antibiotic Susceptibility of Atobium Vaginae (2006)

Prior studies have shown that anaerobic bacterium, Atopobium vaginae had been closely related with Bacterial Vaginosis. There have only been four isolates of this fastidious organism that were found to be highly resistant to metroniadazole and susceptible for clindamycin, two antibiotics preferred for the treatment of Bacterial Vaginosis. The research group studied the susceptibility of nine other A. vaginae isolates for 15 antimicrobial agents by using the Etest and for comparison that included a limited number of other important vaginal bacteria such as lactobacilli, G. vaginalis, bifidobacteria and compared results from previously published articles. The decided method for this particular research involved nine strains of Atopobium vaginaw, four strains of Gardnerella vaginalis, two strains of Lactobacillus iners and one strain each of Bifidobacterium breve, B. Longum, L. Crispatus, L.gasseri and L. jensenii which were tested against 15 antimicrobial agents using the Etest. The conclusion of this research had shown Clindamycin had a higher activity against G. vaginalis and A. vaginae than metronidazole, but not all A. vaginae isolates are metronidazole resistant, that seemed to be an apparent conclusion from previous studies on a more limited number of strains. In addition, the research group had concluded Bacterial vaginosis as a polymicrobial disease and the organisms that were involved were likely to be in a symbiotic relationship to each other for various metabolic requirements. In conclusion, clindamycin was shown to dimish the vaginal colonisation resistancere. However, resistance to clindamycin seems to develop more readily than resistance to metronidazole which becomes apparent from clinical studies comparing both antibiotics.

Future studies will focus on determining the antibiotic suseptibility of the vaginal specie that will shed light to develop new regimens for treatment of recurrent bacterial vaginosis. An important note is to make clear whther this metronidazole resistance might be acquired by the presence and activation of nim-genes [11].

Differences in the Composition of Vaginal Communities of Caucasian and Black Women (2007)

In essence, all females vagina have the same construct. But the question is whether or not race plays a role. In 2007, researchers from the Department of Biological Sciences at University of Idaho conducted a study to see if and how differences in bacterial communities in the vagina differ from Caucasian and Black women; and how these variations could lead to possible infections. The hypothesis was that there indeed are differences in the composition as well as structure of bacterial colonies the vaginas of Caucasian and Black North Americans. In this study, 144 Caucasian and Black women from North America who were healthy, menstruating, not pregnant but are capable of becoming pregnant, and are within the reproductive age, had samples taken near the middle of their vaginas with a sterile swab. These samples were then analyzed. The differences in the vaginal communities between the two races were found by investigating the T-RFLPs of 16S rRNA genes. Depending on the similarities of the composition of the communities, different bacteria were divided into groups called supergroups. After much condensing, the researches finally limited the number of supergroups down to 8 which accounted for 94% of the women sampled. The results from this experiment concluded that the kinds of microbes found in the vaginas of Caucasian women and Black women were very different. Lactobacillus was significantly less prevalent in Black women at 68% than those of Caucasian women at 91%. While certain types of anaerobic bacteria was higher for Black women at 32% compared to Caucasian women at only 8%. They found it super suprising that supergroup III, which included communities of Atopobium sp and other anaerobes, were four times as common in Black women as Caucasian. Overall, the hypothesis that there are differences in the composition as well as structure of bacterial colonies the vaginas of Caucasian and Black North Americans proved true. Researches did not stop after they adequately proved this hypothesis. Recently, studies have been conducted on the appearance of Atopobium in the vaginal of women in their reproductive age and postmenopausal women. From their findings, it suggests that Atopobium is a common vaginal microbe in all healthy women [12].

http://jb.asm.org/cgi/content/full/190/2/727?maxtoshow=&HITS=10&hits=10&RESULTFORMAT=&fulltext=+vagina&searchid=1&FIRSTINDEX=0&fdate=1/1/2006&resourcetype=HWCIT Genome Sequence of Lactobacillus helveticus, an Organism Distinguished by Selective Gene Loss and Insertion Sequence Element Expansion. (2008, January)[10]

Scientists isolated Lactobacillus helveticus, strain DPC4571, from swiss cheese and explored its relationship and similarities with non-dairy Lactobacillus strains found in the human GI tract, specifically Lactidobacillus acidophilus, strain NCFN. DPC4571 was selected due to its reputation for being a healthy, pro-biotic organism. Examination of the complete gene sequences of DPC4571 and NCFN showed conservation of 65-75% of genes and 98.4% of 16S rRNA revealing significant insight for future identification of niche-specific genes. DPC4571 genome comprised of up to ten times more 213 IS elements in comparison to NCFN indicating the significance of gene loss for colonization in the GI tract. NCFN also has half the amount of PTS system, membrane protiens (cell wall adherence proteins), and sugar metabolism compared to DPC4571 due to selective deletions in the genome. Sources of such deletions include point mutations, horizontal gene transfers and transposons. Such genome difference provide insight into gene roles in pro-biotic genomes. [10] above article is currently worked on by eunice ^^

References

(1)Female Genital-Tract HIV Load Correlates Inversely with LactobacillusSpecies but Positively with Bacterial Vaginosis and Mycoplasma hominis Beverly E. Sha, M. Reza Zariffard, Qiong J. Wang, Hua Y. Chen, James Bremer, Mardge H. Cohen, and Gregory T. Spear The Journal of Infectious Diseases 2005 191:1, 25-32

(2) McLean, N. W., and I. J. Rosenstein. 2000 Characterisation and selection of a Lactobacillus species to re-colonise the vagina of women with recurrent bacterial vaginosis J. Med. Microbiol. 49 543–552

(3)The Identification of Vaginal Lactobacillus Species and the Demographic and Microbiologic Characteristics of Women Colonized by These Species May A. D. Antonio, Stephen E. Hawes, and Sharon L. Hillier The Journal of Infectious Diseases 1999 180:6, 1950-1956

(6) Aroutcheva, Alla A, Simoes, Jose A., and Faro Sebastian. 2001 Antimicrobial protein produced by vaginal Lactobacillus acidophilus that inhibits Gardnerella vaginalis

(7) Streptococcal infections : clinical aspects, microbiology, and molecular pathogenesis / edited by De New York : Oxford University Press, 2000. P. 223-230, 183-186.

(8) Contemporary therapy in obstetrics and gynecology / editors, Scott B. Ransom ... [et al.] Philadelphia : W.B. Saunders, c2002. p. 148-151.

(9)Narayanan, S., Levy C. “Streptococcus Group B Infections“. eMedicine. 2006, Mar 24.[6]

(10)Callanan, M., Kaleta, P., O'Callaghan, J., O'Sullivan, O., Jordan, K., McAuliffe, O., Sangrador-Vegas, A., Slattery, L., F. Fitzgerald, G., Beresford, T., and R. Paul Ross “Genome Sequence of Lactobacillus helveticus, an Organism Distinguished by Selective Gene Loss and Insertion Sequence Element Expansion“. Journal of Bacteriology, January 2008, p. 727-735, Vol. 190, No. 2 (11) "Antibiotic susceptibility of Atopobium vaginae"

(12) Differences in the Composition of vaginal microbial communities found in healthy Cacuasian and black women Xia Zhou, Celeste J. Brown, Zaid Abdo, Catherine C. Davis, Melanie A. Hansmann, Paul Joyce, James A. Foster and Larry J. Forney The ISME Journal (2007) pp.121-132 <http://www.nature.com/ismej/journal/v1/n2/full/ismej200712a.html>.

(13) Boris, S., J. E. Suárez, F. Vásquez, and C. Barbés. 1998 Adherence of human vaginal lactobacilli to vaginal epithelial cells and interaction with uropathogens Infect. Immun. 66 1985–1989

Edited by [Jason Wong, Yumi Honda, Elieth Martinez, Raymond Villar, Eunice Kim, Whitney La], students of Rachel Larsen