Vibrio cholerae O1 Biotype El Tor: Virulence Factors

Vibrio cholerae O1 biovar El Tor

Vibrio cholerae (V.cholerae) is a gram-negative pathogenic bacterium that infects the small intestine. Symptoms include severe diarrhea, vomiting, and dehydration, which can be life-threatening if not treated promptly. There are more than 200 serogroups of V.cholerae, but only two – O1 and O139 – are associated with cholera epidemics.[1]

V.cholerae is highly motile, with a single polar flagellum that enables it to move quickly in liquid environments. It circulates between the aquatic environment and the human gut. Direct human-to-human transmission of cholera is rare. Instead, the bacteria survive, proliferate, and transmit via contaminated reservoirs, including rivers, ponds, coastal waters, and wells.[1]

Vibrio cholerae serogroup O1 biotype El Tor (V.cholerae O1 El Tor) was the dominant strain of the 7th global cholera pandemic. It possesses two circular chromosomes that encode for 3,885 total open reading frames (2,770 on Chr 1 and 1,115 on Chr 2). [2] Most essential cell function and pathogenicity genes – including those for DNA replication and toxin production – are on Chr 1. [2] The ability of V. cholerae to cause illness in hosts requires the production of several virulence factors, including cholera enterotoxin, hemolysin toxin, and HA/protease.

Virulence factors — or pathogenicity factors — are structures, molecules, and regulatory systems that enable pathogens to colonize hosts and counter their immune responses [3]

To initiate infection, V.cholerae must traverse the stomach acid and survive among bile and antimicrobial peptides in the small intestines (Ramamurthy et.al, 2020) [2] . El Tor strains have as many as 524 virulence-associated genes. Host immune and biological factors induce several of these survival, colonization, and pathogenicity genes [2] .

Cholera Enterotoxin

Decrease in Prochlorococcus Functionality

Two more critical virulence factors of V. cholerae El Tor are the cholera toxin (CT), which causes severe diarrhea, and toxin-coregulated pilus (TCP), a type of IV pilus critical for intestinal colonization (Weber and Klose, 2011). ToxT is the direct transcriptional activator for both genes encoding CT (ctxAB) and TCP. ToxRS and TcpPH activate the expression of ToxT in response to environmental signals (Weber and Klose, 2011).

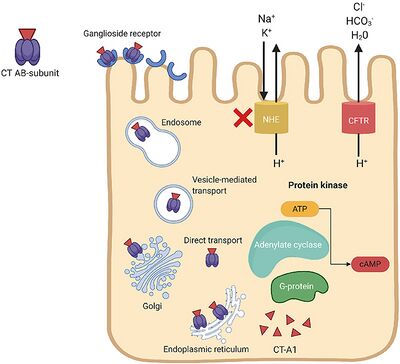

encoded on CTXϕ phages. Cholera toxin consists of an A subunit, responsible for enzymatic activity, and five B subunits, which bind to specific receptors on the surface of intestinal epithelial cells. Upon binding, the toxin is internalized into the host cell, where the A subunit exerts its effects by activating adenylate cyclase, leading to the uncontrolled secretion of chloride ions and water into the intestinal lumen. This results in the characteristic watery diarrhea observed in cholera cases, leading to dehydration and electrolyte imbalance if left untreated

Cholera toxin is a potent bacterial toxin produced by Vibrio cholerae, the bacterium responsible for causing cholera. The toxin plays a central role in the pathogenesis of cholera, a severe diarrheal disease. It consists of two subunits: the A subunit (active subunit) and the B subunit (binding subunit). The B subunit is responsible for binding to specific receptors on the surface of intestinal cells, facilitating the entry of the toxin into the cell. Once inside the cell, the A subunit becomes activated and catalyzes the transfer of ADP-ribose from NAD+ to the Gs protein, a key component of the adenylate cyclase complex. This leads to the constitutive activation of adenylate cyclase, resulting in an uncontrolled increase in intracellular levels of cyclic AMP (cAMP). Elevated levels of cAMP disrupt ion transport mechanisms in the intestinal epithelium, leading to the secretion of electrolytes and water into the intestinal lumen. This excessive fluid loss manifests clinically as profuse watery diarrhea, a hallmark symptom of cholera. If left untreated, severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalances can occur, leading to shock, organ failure, and death.

Hemolysin Toxin

The ability of V. cholerae to cause illness in hosts requires the production of several virulence factors. For instance, the HlyA gene on Chr 2 codes for a hemolysin toxin. Hemolysin causes blood cell lysis and cytoplasmic vacuolization and is believed to cause lethality and developmental delays in Caenorhabditis elegans infected with V. cholerae (Gao et.al, 2018). HlyA expression is regulated by quorum sensing and regulatory proteins HapR, HlyU, and Fur (Gao et.al, 2018). In the early-to-mid-log phase, HlyU binds to the HlyA promoter to activate its transcription. In late log phase, HapR binds to the Fur, HlyU, and HlyA promoters to repress their transcription (Gao et.al, 2018). HlyA promotes bacterial invasion in the early stages of infection.

HA/protease

V. cholerae also expresses Hemagglutinin/protease (HA/protease). HA/protease is involved in several pathogenic activities, including the modification of other toxins and the degradation of the protective mucus barrier in the gut (Benitez and Silva, 2017). The hapA gene encodes for HA/protease. The transcription of hapA activates under limited nutrient conditions, at high cell population density, and in stationary phase (Benitez and Silva, 2017). Transcription of hapA requires the quorum sensing regulator HapR and RpoS. For example, limited nutrients lead to an increase in intracellular cAMP, which activates RpoS and CRP. CRP then activates HapR (Benitez and Silva, 2017).

toxin-coregulated pilus

Additionally, V. cholerae has become a multidrug-resistant pathogen. The primary cause of V. cholerae drug resistance is the acquisition of extrachromosomal mobile genetic elements (Das, 2020). Sequencing of the genome of clinical and environmental V. cholerae strains has revealed various genetic elements that encode antimicrobial resistance, including integrating conjugative elements, transposable elements, and insertion sequences (Das, 2020).

Conclusion

The genome of Vibrio cholerae enables it to be a highly dangerous pathogen. The bacterium releases various virulence factors, such as hemolysin toxin, cholera toxin, toxin-coregulated pilus, and HA/protease. As the bacterium becomes more multidrug-resistant, Vibrio cholerae will likely continue to pose a worldwide health threat.

Cholera (the disease caused by V. cholerae) has been a public health concern for centuries. Despite sanitation and medical advancements, cholera remains a threat in many areas of the world, particularly those with inadequate sanitation and poor access to clean water. Cholera outbreaks occur regularly in parts of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, and the Middle East. Proper sanitation, clean water, Surveillance systems, and prompt treatment with rehydration therapy are essential for managing and preventing cholera outbreaks.

References

At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki.

The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: PHIL_1181_lores.jpg

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Magnified 20,000X, this colorized scanning electron micrograph (SEM) depicts a grouping of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria. Photo credit: CDC. Every image requires a link to the source.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Sample citations: [4]

[5]

A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes.

To repeat the citation for other statements, the reference needs to have a names: "Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ramamurthy, T. N.,et al. “Virulence Regulation and Innate Host Response in the Pathogenicity of Vibrio cholerae." Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, Vol. 10, 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Heidelberg, J. F.,et al. “DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae.” Nature, Vol. 406, Issue 6795, 2000, pp. 477–483.

- ↑ Casadevall, Arturo and Pirofski, Liise-anne. "Virulence factors and their mechanisms of action: the view from a damage–response framework." Journal of Water and Health, Vol. 7, Issue S1, 2009, pp. S2–S18.

- ↑ Hodgkin, J. and Partridge, F.A. "Caenorhabditis elegans meets microsporidia: the nematode killers from Paris." 2008. PLoS Biology 6:2634-2637.

- ↑ Bartlett et al.: Oncolytic viruses as therapeutic cancer vaccines. Molecular Cancer 2013 12:103.

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski,at Kenyon College,2024