Vinification, flavor, and aroma

Wine making, or vinification is a process, through which fruit juice, usually from grapes, is fermented to produce an alcoholic drink. Once fruit is harvested, it is the wine makers duty to ferment the juice into a palatable wine through complex interactions of yeast and bacteria. Fermentation can be achieved using the natural grape must, naturally occurring yeast on machinery and vines, or by inoculating batches with commercially produced yeasts. Vinification requires the careful management of the microflora present, nutrient availability for the microflora, pH, temperature, and storage conditions, in order to make a palatable vintage.

The perception of a wine’s flavor and aroma comes from a multitude of interactions between about a 1,000 chemical compounds within the wine and our own sensory receptors. These chemical compounds function in many different ways, and can act synergistically or antagonistically with each other. Flavor and aroma compounds are derived from the grapes themselves, the wood fermentation occurs in, and the metabolites of microbes used in the fermentation process. Making a tasty wine is largely related to the ratios of volatile compounds found in the wine; wines with out enough of a certain compound will lack flavor and fullness, while wines with too much of a compound can taste spoiled. These compounds result from both the alcoholic fermentation process and the malolactic fermentation, which both involve their own microbes.

One other aspect of wine flavor and aroma comes from yeast assimilable nitrogen. Yeast assimilable nitrogen (YAN) is the amount of nitrogen available for yeast during the fermentation process. YAN is inherent to grapes, and can be measured after harvesting and crushing, but can also be controlled by the wine maker to reduce the likelihood of spoilage.

Microbial Processes of Vinification

Alcoholic Fermentation

Malolactic Fermentation

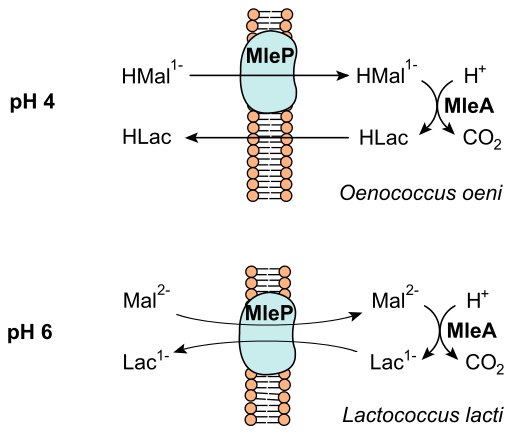

The secondary phase of fermentation is known as malolactic fermentation. Malolactic fermentation is the decarboxylation of L-malic acid to L-lactic acid through enzymatic activity. Several lactic acid bacteria can be responsible for malolactic fermentation, with varying effects on the wines flavor and aroma. Lactic acid bacteria in grape must come from the gnera Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Leuconostoc, and Oenococcus. [1]

At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki. The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: Ebola virus 1.jpeg

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Electron micrograph of the Ebola Zaire virus. This was the first photo ever taken of the virus, on 10/13/1976. By Dr. F.A. Murphy, now at U.C. Davis, then at the CDC.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Overall paper length should be 3,000 words, with at least 3 figures with data.

Compounds That Effect Flavor and Aroma

Hydrogen Sulfide

Yeast has role in production of volatile sulfur compounds through the sulfate reduction sequence pathway. The importance of sulfur compounds in wine has a tremendous effect on the sensory quality of the wine. Hydrogen sulfide can make wines smell rotten while other sulfur compounds like the flavor active thiol 3-mercaptohexanol, can impart fruity notes beneficial to the sensory quality of a wine. The wine yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is responsible for forming many of these volatile sulfur compounds that contribute to a wines sensory quality.

Hydrogen sulfides found in wine are formed through the metabolic pathways of yeast from inorganic sulfur compounds, sulfate and sulfite, and from organic sulfur compounds cysteine and glutathionine. Hydrogen sulfide is released from the cell as result of the sulfate reduction sequence pathway. Hydrogen sulfide is derived from the HS- ion, which serves as an intermediate stage in the reduction of sulfite and sulfate to synthesize organic sulfur compounds. The HS- ion is sequestered in the presence of a nitrogen supply to form methionine and cysteine. Thus in low nitrogen environments, sulfide gathers within the cell and be released as hydrogen sulfide.

Yeast Assimilable Nitrogen and Free Amino Nitrogen

One particular aspect of wine making includes overcoming the variability of grape juice from year to year. Depending on the season and climate, grapes can have different sugar, amino acid, and nitrogen compositions. The interplay between these and other major compounds is what winemakers attempt to fine tune in order to create one palatable vintages year after year with changing grape conditions.

Yeast assimilable nitrogen (YAN) is important for any beverage fermentation process. YAN refers to the nitrogenous compounds like Free Amino Nitrogen (FAN), ammonia, and ammonium available in grapes. The most important sources of nitrogenous compounds are alpha amino acids, ammonium ion concentrations and small peptides, excluding Proline a dominant secondary amino acid. Among Australian grape juices YAN can vary from 50-350 mg/L. Yeast also varies in its metabolic demand for nitrogen. Besides fermentable sugars, nitrogen availability is the primary nutrient in yeast fermentation. YAN can be measured after harvest, depending on the level of facilities available. Controlling YAN is critical to all wine making to ensure spoilage organisms don’t ruin the wines sensory quality. Lack of YAN can be the cause of things like stuck fermentations, where yeast stop metabolizing and enter a dormant state. Diammonium phosphate can be added as a nutrient to correct for YAN levels, often at the beginning of the fermentation process.

Free amino nitrogen is assimilable, or available, to yeast for metabolic activity during the fermentation process. Thus because nitrogen availability is so strongly tied good fermentation, the amount of FAN is of interest to enologists. FAN is determined by assaying the alpha amino group of primary amino acids, or FAN. Proline is exluded from the assay because though it contains FAN, the nitrogen in Proline is not assimilable in aerobic fermentation environments. The measurement of non-Proline FAN and combined with the measurement of ammonia by enzymatic method is a sophisticated method for measuring YAN. Simpler methods for measuring YAN include the Formal Titration, and more complex ones like mid-infrared spectrometry.

Many different wine compounds derived from fermentation are regulated by YAN. These compounds vary due to YAN levels and yeast species. Primary metabolites of sugar metabolism are controlled by YAN levels. Ethanol is another major product of sugar fermentation but generally, YAN has little effect on the ethanol yield. Glycerol and acetic acid are strongly dependent on both initial YAN levels, and yeast strain used. Sulfur dioxide production is also stimulated by initial YAN concentrations, but is shown to be largely yeast species dependent. Malolactic fermentation inhibition is also associated with high YAN levels, but not SO2 production (Osborne and Edwards 2006).

Higher alcohols in wines contribute to the complexity of a wines aroma and flavor, but high concentrations of higher alcohols may hide the wines fruity charateristics. Fatty acids ethyl esters and acetate contribute to the fruity wine aromas.

Future YAN applications & methods

Researchers have begun to assess ways to best control YAN in the industrial winemaking process. Yeast is shown to produce key aroma compounds, esters, alcohols, acids and lactones. One study examined two yeast strains that created different wines under initial nitrogen conditions to test the common practice of adding YAN before identifying levels of naturally occurring YAN.

Further Reading

[Sample link] Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever—Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Special Pathogens Branch Further reading:

References

[www.ftb.com.hrfiles/journals/1/articles/183/public/183-182-1-PB.pdf Romano, Patrizia. "Metabolic characteristics of wine strains during spontaneous and inoculated fermentation." Food Technology and Biotechnology 35 (1997): 255-260.]

Edited by Patrick Niedermeyer, a student of Nora Sullivan in BIOL168L (Microbiology) in The Keck Science Department of the Claremont Colleges Spring 2014.