Biofilms on food preparation surfaces

Introduction

Biofilms are a consortium of microorganisms and extracellular substances in association with a solid surface in contact with liquid. It is nature of microorganisms to attach to wet surface, and form slimy layer composed of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) to protect themselves from grazers and harsh environment. Biofilms can be beneficial or detrimental to the environment on which they form. For example, stream biofilm is capable of recycling organic matter. On the other hand, biofilms forming on food-contact surfaces can lead to hygienic problems and economical losses due to food spoilage. Food-contact surfaces can be a great habitat for food-borne pathogens because food preparation surfaces are usually in contact with organic matter such as milk which is a good source of nutrients for microorganisms, with inorganic debris, with other microorganisms. Once bacteria irreversibly attach to the surface, they produce EPS, which helps bind cells together, to the surface, and to other particulate materials. Cells also communicate between themselves to initiate antibiotic biosynthesis, and extracellular enzyme biosynthesis.

Physical Environment

Physical properties of the environment are essential for microorganism attachment to the substratum, biofilm formation ,and microbial processes. For example, food conditioning surfaces may promote the attachment of bacteria. The pH and temperature also affect microbial metabolism processes. Some of the physical conditions are described below.

Conditioning of a Surface

Biofilm formation can occur on any submerged surfaces in any environment with the present of bacteria. On food preparation surfaces, bacteria, inorganic and organic materials get adsorb on the surface in minutes of substratum immersion into liquids leading to conditioning surfaces. In food industry, this conditioning film may be proteins from milk or meat. Protein from milk was studied to adsorb to numbers of food-contacting surfaces such as Teflon, stainless steel, and aluminosilicate[10]. The conditioning can alter physio-chemical properties of the surface, surface charge, surface free energy, surface hydrophobicity, which further results in bacterial attachment on the surface[7].

Surface Charge and Hydrophobicity

Surface charge and hydrophobicity of both bacterial cells and a conditioning surface play an important role in microbial attachment on the surface. These two factors have an impact on the length of time cells are associated with the substratrum. Surface charge results in electrostatic interaction between 2 surfaces. Moreover, cell surface hydrophobicity is also important in adhesion because hydrophobic interaction tends to increase with increasing non-polar property of each surface.

Surface Topography

The relationship between surface roughness and the attachment and growth of bacteria may vary. It was shown that two strains of Yersinia have a strong correlation between the roughness amplitude of the substratrum and adhesion. On the other hand, another showed that little correlation was found on attachment of streptococci to stainless steel.

pH and Temperature

The pH and temperature of a contact surface govern many physical and biological processes of bacterial cells. It was studied that the maximum adhesion of Pseudomonas fragi to stainless steel surfaces was at the pH range of 7 to 8, which was also optimum for cell metabolism. Another study showed that Yersinia enterocolitica attached to stainless steel surfaces better at 21 °C than at 35 °C or 10 °C.

Oxygen Availability and Moisture

The structure of biofilms has a porous structure with a number of capillary water channel within which water and nutrients are transported through. It is believed that these capillaries are responsible for oxygen transport to the inner areas of biofilms. Unfortunately, due to oxygen limited diffusion ability and oxygen consumption, the inner areas encounter low oxygen concentration or anaerobic condition. This phenomenon explains why aerobic and anaerobic bacteria can live together in biofilms.

Stainless Steel as a Food Source Contact Surface

Stainless steel is the most common food contact surface used in the food industry. Stainless steel is suitable for the food industry because of the stability of physical and chemical properties at a various processing temperature. It is highly resistant to corrosion and easy to clean. However, if taking a look at microscopic level of stainless steel surface, it is amazing that stainless steel is composed of cracks and crevices. These structures are different from macroscopic appearance. Such topography allows bacteria and organic substances from food to attach. Studies have shown the attachment of food-borne pathogens and spoiled microorganisms to stainless steel.

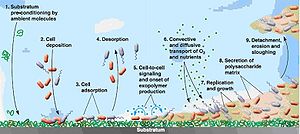

Biofilm Formation

Biofilm formation includes a sequence of steps as shown in a picture below. The biofilm formation process is fairly slow and reaches a millimeter thick in days according to culture conditions. Due to difference in nutritional requirements, composition of biofilms is not homogeneous, and the microorganisms withing biofilms distribute non-uniformly. Increase in the size of biofilms can take place by the deposition of other organic and inorganic substances, or other microorganisms. On the other hand, sloughing and detachment can lead to decrease in size of biofilms.

Biological Interactions

Cell-Cell Communication

Bacterial community development involves self-organizing and cell cooperation. Within biofilms, different bacterial communities cooperate with each other rather than compete. This concept becomes particular in study of biofilms. Cell-cell signaling may play an important role in microorganism attachment and detachment from biofilms. The successful adaptation of bacteria to the changing environment depends on the ability of themselves to sense and respond to the external environment and regulate gene expression accordingly.

Quorum Sensing

Quorum sensing is based on an auto-induced process.The process of quorum provides cells with a self-organizing mechanism and gene regulation. The quorum sensing begins with bacteria monitor and feel the environment. After that bacteria may produce a diffusible organic signal molecule which accumulates in the surrounding environment during the growth. High cell densities result in high concentration of signal. High signal concentration can induce gene or physiological changes in neighboring cells. Therefore, a respond to signal by bacteria in the environment is dependent on signal concentration.

Quorum sensing involves in a range of important microbial activities. These activities include biofilm formation, biofilm development, antibiotic synthesis, extracellular enzyme biosynthesis, EPS synthesis and extracellular virulence factors in Gram-negative bacteria.

Coaggregation and Aggregation

The abilities of biofilms to form correlate with the ability to aggregate in liquid culture. Similar phenotypes tend to autoaggregate and clump. Coaggreagation enables cells to withstand the highly changing environment, which on the other hand can adversely affect monodispersed cells. Coaggregation usually refers to adhesion between genetically distinct microorganisms. These distinct bacteria are bound together by specific molecules. Coaggregation in biofilms is important in development of mix-culture biofilms.

Conjugation

The study of Gram-negative bacterium E. coli in biofilm development lead to the finding that conjugative pili might act as cell adhesin interconnecting and stabilizing biofilm structure. This cell-cell attachment is based on plasmid-encoded and is subject to conjugal gene transfer. Dissemination of these plasmids among bacterial cells can enhance biofilm formation, biofilm development, and can strengthen the stability of the biofilm structure. Conjugation may be another mechanism that bacteria develop to transfer plasmid to the adjacent cells. Therefore, many cells in the ecosystem will acquire and express the biofilm attributes. This process could be a mechanism that bacteria develop to rapidly and effectively expand the ecosystem. Conjugal process is also independent of quorum sensing signal.

Microbial Processes

Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS)

After the initial contact with the surface, bacteria start to produce thin fiber layer. This fiber layer is called extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). EPS act as glue to bind cells and other particulates and to adhere cells to the surface. Bacterial EPS are mainly composed of polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, phospholipids, and humic substances. Polysaccharides and proteins are the main composition of EPS approximately 75-89%.

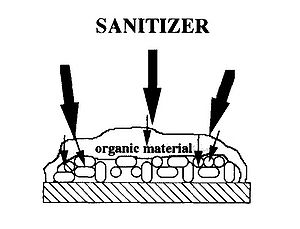

A gel phase is formed in biofilms in which bacteria live. The EPS matrix acts as a barrier against adverse conditions. For example, biofilms are observed to be able to tolerate high concentrations of biocides. The EPS layer delays or prevents diffusion of antimicrobial solution from reaching target microorganisms. Moreover, within EPS matrix, cell-cell signaling molecules may accumulate upto high concentration, which in turn can be effective.

Horizontal Gene Transfer

Biofilms provide the suitable environment for gene transfer. Horizontal gene transfer occurs more efficiently in biofilms than in suspended cells because cells are in contact with each other. This gene transfer process includes conjugation and transformation. Gene transfer can be affected by quorum sensing signals which facilitate cell competence development.

Key Microorganisms

Most of the key microorganisms associate with biofilms formed on food contact surfaces are bacteria. Some of them are food-borne pathogens which can pose a health risk for consumers. Moreover, these biofilms can lead to energy loss, food spoilage, and loss in energy. Bacteriophages are also detected in the biofilm.

Listeria monocytogenes

L. monocytogenes is one of the important food-borne pathogens that cause severe illness (listeriosis) in immuno-compromised people. It can grow in a wide range of temperature from 1 to 45 °C, and at broad acidity levels from pH 4 to 9. This versatile ability enable L. monocytogenes to outcompete other bacteria in extreme conditions. It is quite dangerous to foods that are stored at refrigerator temperatures, because these psychrophilic bacteria can multiply and thrive during storage. It is usually found in dairy products.

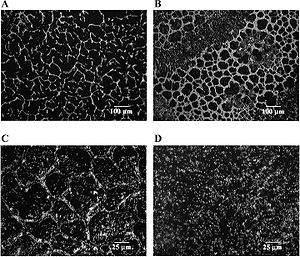

An individual strain known as persistent strain of L. monocytogenes involves in biofilm formation in food facility. These bacterial biofilms enable L. monocytogenes to repeatedly appears in the same facility over a month or even a year. As we learn, once bacteria form biofilms, they are more resistant to antimicrobial products and cleaning processes. Marsh et.al studied the formation of L. monocytogenes biofilms upto 72 hr. The structure is distinctively developed like "honeycomb" network. L. monocytogenes is also found to attach to the surface of stainless steel in slurry in fishery industry.

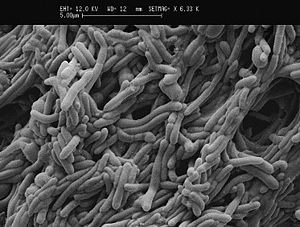

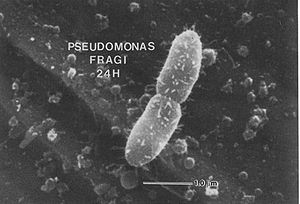

Pseudomonas

Pseudomonas spp. is long known to be one of the bacteria that can cause spoilage of pasteurized liquid milk. First, it produces lipolytic and proteolytic enzymes and excretes them into raw milk in a pre-pasteurizing process. These enzymes can be generated even in psychrotropic environments, and they can tolerate unusual high temperature during pasteurization, which reduces the shelf-life of the product. Second, Pseudomonas spp. can also cause spoilage to milk after processing. Pseudomonas fragi is found to be able to grow on stainless steel with thread-like structures. These special structure may help in adhering the cell to the surface and even may be essential in biofilm formation.

Bacteriophage in Biofilms

A bacteriophage is one of the viruses that infect bacteria. Bacteriophages are found common as biological entities on earth. Even though there are few studies on interaction of bacteriophage with biofilms, there was a report that bacterial viruses could infect starter culture in cheese industry. The starters lysed as the production of acid in the cheese vats decreased rapidly. Biofilms in cheese industry are important. Many food contact surfaces such as pipe work, floor drains, and tanks involving in whey disposal can suitably host biofilm growth. It was shown that the cheese starter was able to form biofilms on stainless steel, and equilibrium between cells and bacteriophages was established. Phages lysed bacterial cells causing them to die. These dead cells might promote the persistent and survival of neighboring cells due to nutrient transfer. However, further studies have to be done in order to thoroughly understand bacteriophage behaviors in biofilms.

Examples of organisms within the group

Biofilms on food contact surfaces are usually multispecies. Mixed culture biofilms are normally thicker and more stable than single species biofilms. Biofilms can be composed of bacteria and/or bacteriophage. Cells in biofilms distribute themselves based on the ability survive the different microenvironment within the substratrum. For example, in the inner part of biofilms, anaerobic bacteria can thrive and grow, while aerobic bacteria stay in the outer layer where oxygen availability is higher. Organisms in multispecies are not randomly organized, but rather arrange themselves in a way to benefit the most.

Current Research

Cleaning and Removal of Biofilm

Once the biofilms form on food contact surface, they are quite resistant to antimicrobial agents because of slimy layer formed by bacteria. It is essential to find economical and efficient ways to clean and disinfect those surfaces. The disinfectant must be effective, safe, and easy to use[2][7][10]. Besides chemical methods, biological control can be used to eliminate biofilms. Bacteriophages are studies in this case. However, there are still limited studies on this field. Last but not least, mechanical treatments can also be employed with chemical agents to disinfect and remove biofilms. For instance, air-injected CIP system is a combination between physical and chemical processes used to remove biofilms in milking systems[6].

Microscopic Examination of Biofilms

Biofilms are usually heterogeneous resulting in a specimen that is difficult to visualize. The thickness, the shape, or either the surface to which biofilms are attached, can be a challenge in biofilm study. A number of microscopic techniques such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), atomic force microscopy (AFM), and confocal scanning laser microscopy (CSLM) can be used to image biofilms. Some of the recent research have been focusing on analyzing biofilm structure, bacterial communities, and cell surfaces by using thes microscopic techniques[3][10][11].

Attachment of Microorganisms on Food Contacting Surfaces

Microbial cell attachment to food contacting surfaces is one of the important processes in biofilm formation. A thermodynamic study showed that hydrophobicity of both cells and substratrum affect bacterial attachment. Moreover, the structure of conditioning films which are the result from organic matter, debris, and inorganic matter adsorbing on the surface can promote the attachment. Temperature, pH, electrolytes, and non-electrolyte are also important factors that in turn affects hydrophobicity and surface charges.

References

1.Simoes, M.; Simoes, L. C.; Vieira, M. J., A review of current and emergent biofilm control strategies. Lwt-Food Science and Technology 2010, 43 (4), 573-583.

2.Brooks, J. D.; Flint, S. H., Biofilms in the food industry: problems and potential solutions. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2008, 43 (12), 2163-2176.

3.Marsh, E. J.; Luo, H. L.; Wang, H., A three-tiered approach to differentiate Listeria monocytogenes biofilm-forming abilities. Fems Microbiology Letters 2003, 228 (2), 203-210.

4.Sharma, M.; Anand, S. K., Bacterial biofilm on food contact surfaces: A review. J. Food Sci. Technol.-Mysore 2002, 39 (6), 573-593.

5.Poulsen, L. V., Microbial biofilm in food processing. Food Science and Technology-Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft & Technologie 1999, 32 (6), 321-326.

6.Wong, A. C. L., Biofilms in food processing environments. Journal of Dairy Science 1998, 81 (10), 2765-2770.

7.Kumar, C. G.; Anand, S. K., Significance of microbial biofilms in food industry: a review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1998, 42 (1-2), 9-27.

8.Davies, D. G.; Parsek, M. R.; Pearson, J. P.; Iglewski, B. H.; Costerton, J. W.; Greenberg, E. P., The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science 1998, 280 (5361), 295-298.

9.Surman, S. B.; Walker, J. T.; Goddard, D. T.; Morton, L. H. G.; Keevil, C. W.; Weaver, W.; Skinner, A.; Hanson, K.; Caldwell, D.; Kurtz, J., Comparison of microscope techniques for the examination of biofilms. Journal of Microbiological Methods 1996, 25 (1), 57-70.

10.Zottola, E. A.; Sasahara, K. C., MICROBIAL BIOFILMS IN THE FOOD-PROCESSING INDUSTRY - SHOULD THEY BE A CONCERN. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1994, 23 (2), 125-148.

11.Wang, H. H. B., Hans P.; Agle, Meredith E. , Biofilms in the food environment. Blackwell: Ames, Iowa 2007; p 194.

Edited by student of Angela Kent at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.