Lactobacillus delbrueckii: Difference between revisions

(Undo revision 21837 by Special:Contributions/Mpenetra (User talk:Mpenetra)) |

(Added an image.) |

||

| (6 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Uncurated}} | |||

{{Biorealm Genus}} | {{Biorealm Genus}} | ||

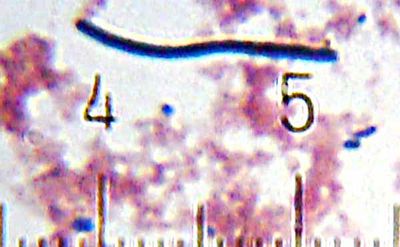

[[Image:20101210_014809_LactobacillusBulgaricus.jpg|thumb|400px|right|<i>Lactobacillus delbrueckii</i> subspecies <i>bulgaricus</i><br/>Numbered ticks are 11 µM apart.<br/>[[Gram staining|Gram-stained]].<br/>Photograph by [[User:Blaylock|Bob Blaylock]].]] | |||

==Classification== | ==Classification== | ||

| Line 12: | Line 14: | ||

'''NCBI: [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Tree&id=2&lvl=3&lin=f&keep=1&srchmode=1&unlock Taxonomy]''' | '''NCBI: [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Tree&id=2&lvl=3&lin=f&keep=1&srchmode=1&unlock Taxonomy]''' | ||

|} | |} | ||

''Lactobacillus <i>delbrueckii</i>'' | |||

<i>subspecies: bulgaricus, lactis, delbrueckii, and indicus </i> | |||

==Description and significance== | |||

<i>Lactobacillus us delbrueckii</i> is a rod shaped, gram positive, non-motile bacterium. Common to the species is its ability to ferment sugar substrates into lactic acid products under anaerobic conditions. As such, <i>L. delbrueckii</i> are generally found in dairy products such as yogurt, milk, and cheese with the exception of <i>L. delbrueckii</i> subsp. delbruecki which reside in vegetable sources (3). There are four subspecies differentiated by its metabolites and its internal genetics known to date. The most recent accepted subspecies, <i>L. delbrueckii</i> subsp. <i>indicus</i> was isolated from an Indian dairy (1). In contrast, Dr. Stamen Grigorov isolated <i>L. delbrueckii</i> subsp. <i>bulgaricus</i> from a yogurt sample in 1905.<br> | |||

The properties that define <i>L. delbrueckii</i> as a homofermentive lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are not confined by its metabolic end product D-lactate and L-lactate. <i>L. delbrueckii</i> subsp. <i>bulgaricus</i> has been proven to have probiotic affects on humans and animals which include improved lactose tolerance and its ability to stimulate immune responses (4, 5, 7). Past debates against this information questioned the ability of the latter to survive within low acidic environments and the gastric juices of the human gastrointestinal tract. A phosphopolysaccharide produced by <i>L. delbrueckii</i> subsp. <i>bulgaricus</i> has the capability to enhance phagocytosis of macrophages in mice (4).<br> | |||

==Genome structure== | ==Genome structure== | ||

The circular genome of <i>Lactobacillus delbrueckii</i> subsp. <i>bugaricus</i> ATCC 11842 was completed in May of 2006. Composed of 1,864,998 nucleotides, it has an unusually high G-C content (49%) in comparison to other species of the genus <i>Lactobacilli</i> to which it belongs. Of the 2,217 genes present 1,562 code for proteins and 533 as pseudo genes (10). Genomic features such as these, as well as insertion sequence patterns are indicative of its adaptation in the dairy industry and support the theory of a rapid evolutionary phase (11).<br> | |||

Of the 1,562 genes that code for proteins prtB and the lac operon are important to the homofermentative properties of <i>L. delbrueckii</i>. Within the <i>lac</i> operon is the <i>lac</i>S, <i>lac</i>Z, and <i>lac</i>R genes that encodes for the uptake and breakdown of lactose.(3) The <i>lac</i>S gene codes for lactose permease responsible for the ability to transport lactose in through the membrane. The important enzyme B-galactosidase necessary for lactose metabolism is encoded in the <i>lac</i>Z gene. Downstream of <i>lac</i>Z is the regulatory gene <i>lac</i>R.<br> | |||

==Cell structure and metabolism== | ==Cell structure and metabolism== | ||

As a gram positive bacterium <i>L. delbrueckii</i> retains its purple stain under the Gram test. Unique to microbes of this type is a thick cell wall and a cell membrane. The absence of an outer membrane which functions as an additional barrier could be a reason for its sensitivity to bacteriophage attacks (2).<br> Proteases encoded by the prtB gene are found anchored along the cell wall of <i>L. delbrueckii</i> subsp. <i>bulgaricus</i> and <i>lactis</i> ; and most likely in the subsp. <i>indicus</i>. The ability of the subspecies’ to grow in dairy is owed to the enzymatic activity in casein breakdown to expose essential amino acids, in addition, to constitutive or inducible expression of the lacZ gene. (8,4)<br> | |||

Significant to the four <i>L. delbrueckii</i> subspecies are the number and types of substrates it can metabolize. As noted, such properties are restricted to enzyme expression within its genome. <i>L. delbrueckii</i> subsp. <i>bulgaricus</i> and subsp. <i>indicus</i> can metabolize lactose, glucose, fructose, and mannose. In addition to these, <i>L. delbrueckii</i> subsp. <i>lactis</i> catabolizes galactose, sucrose, maltose, trehalose and other modified carbohydrates.(4)<br> | |||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

As an inhabitant of fermented dairy products and producers of lactic acid <i>Lactobacillus delbrueckii</i>, with the exception of <i>L.</i> subsp. <i>delbrueckii</i>, is the cause of its low acidic environment. The nutritional requirements are adapted to the bacterium’s environment; as such includes but are not limited to amino acids, vitamins, carbohydrates and unsaturated fatty acids (9). <i>L. delbrueckii</i> has an optimal growth temperature of 40-44 °C under anaerobic conditions(3). Specifically, <i>L.</i> subsp. <i>bulgaricus</i> has a symbiotic relationship with <i>Streptococcus thermophilus</i> as it coexists in starter lactic acid bacteria cultures.<br> | |||

==Pathology== | ==Pathology== | ||

<i>Lactobacillus delbrueckii</i> is non-pathogenic. In fact, it is widely used in the food industry and can be found in yogurts, milks, vegetables, and cheeses. | |||

==Application to Biotechnology== | ==Application to Biotechnology== | ||

Of the four subspecies known to date <i>L. delbrueckii</i> subsp. <i>bulgaricus</i> and subsp. <i>lactis</i> are most important to the dairy industry, as starter cultures for the production of fermented milk, yogurt, and cheese. Economic losses would be significant if the fermentation process of the widely used <i>Lactobacillus delbrueckii</i> subsp. <i>bulgaricus</i> and subsp. <i>lactis</i> were hindered. Thus, the dairy industry must be able to detect bacteriophages and adjust conditions of production to ensure high quality for safety and shelf life (2). Due to the symbiotic relationship of <i>L. delbrueckii</i> subsp. <i>bulgaricus</i> with <i>Streptococcus thermophilus</i> the latter has been examined simultaneously.<br> | |||

==Current Research== | ==Current Research== | ||

Specific strains of <i>Lactobacilli</i> has been shown to have mitogenic effects and aid in spleen cell proliferation. Heat treated YS strains of <i>L. delbrueckii</i> subspecies <i>bulgaricus</i> and <i>L. acidophilus</i> directly induced generation of IgM and IgG by murine spenocytes and was dependent on bacterium concentrations in contrast to ATCC strains. The former was most effective at amounts of 5×106 and 2 × 107 Lactobacilli ml–1. Antibody concentrations were determined with ELISA and Fisher’s test. In addition, strains YS and ATCC of both Lactobacilli species induced lymphocyte proliferation. <i>L. delbrueckii</i> subsp. <i>bulgaricus</i> was shown to activate polyclonal B-cells indicated from the maintenance of high antibody levels upon removal of Lactobacilli antibodies. (13)<br> | |||

A study suggested the practical use of multiplex PCR to detect bacteriophages at any stage of manufacture. The method proved to be simple and quick, all the while guaranteed the minimum quality requirements of the products. Although results indicated low amounts of <i>L. delbrueckii</i> phages in the samples used, a relatively higher amount was found of <i>S. thermophilus</i> phages. These results are consequent of the increasing proportion of <i>S. thermophilus</i> used in starter cultures. (2)<br> | |||

<i>Lactobacillus delbrueckii</i>, generally, can not be found outside starter cultures in the dairy industry. The natural environment from which it originated is not known for sure. A recent study reported the isolation and characterization of <i>L. delbrueckii</i> subsp. <i>bulgaricus</i> along with its symbiont <i>Streptococcus thermophilus</i> from plants in Bulgaria on the basis of tradional yogurt preparation. Six hundred sixty five plant samples, with the target plant Cornus mas were collected from four sites away from human habitation. Identification of the <i>L.</i> subsp. <i>bulgaricus</i> was determined via phenotype analysis, Pulse field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis, and PCR methods. The cultures samples that grew at 45°C were rod shaped, produced D-lactate, generated a DNA fragment of 1065 base pairs with the primers LB1/LLB1, and showed proteolytic activity. From the 665 plant samples <i>L. delbrueckii</i> subsp. <i>bulgaricus</i> and or <i>S. thermophilus</i> were isolated, a majority of which came from Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria. (12)<br> | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

1) [http://ijs.sgmjournals.org/cgi/content/full/55/1/401Dellaglio, F., Felis, Giovanna E., Castioni, A., Torriani, S., and Germond, J. “Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. indicus subsp. nov., isolated from Indian dairy products”. 2005. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. Volume 55. p. 401-404.] <br> | |||

2) [Del Rio, B., Binetti, A.G., Martın, M.C., Fernandez, M., Magadan, A.H., and Alvarez, M.A. “Multiplex PCR for the detection and identification of dairy | |||

bacteriophages in milk”. Food Microbiology. 2007. Volume 24. p.75-81. ] <br> | |||

3) [http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/20/1/93Germond, J., Lapierre, L., Delley, M., Mollet, B., Felis, G., and Dellaglio, F. “Evolution of the Bacterial Speies Lactobacillus delbrueckii: A Partial Genomic Study with Reflections on Prokaryotic Species Concept”. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2003. Volume 20. p. 93-104. ]<br> | |||

4) [Kitazawa, H., Yasuyuki, I., Uemura, J., Kawai, Y., Saito, T., Kaneko, T., Noda, K., and Itoh, T. “Augmentation of macrophage functions by an extracellular phophopolysaccharide from Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus”. Food Microbiology. 2000. Volume 17. p.109-118. ]<br> | |||

5) [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1489325#r1Elli, M., Callegari, M., Ferrari, S., Bessi, E., Cattibelli, D., Soldi, S., Morelli, L., Feuillerat, N., and Antoine, J. “Survival of Yogurt Bacteria in the Human Gut”. Applied Environmental Microbiology. 2006. Volume 72. p.5113-5117. ]<br> | |||

6) [Perea Velez, M., Hermans, K., Verhoeven, T.L.A., Lebeer, S.E., Vanderleyden, J., and De keersmaecker S.C.J. “Identification and characterization of starter lactic acid bacteria and probiotics from Columbian dairy products”. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2007. Volume 103. p. 666-674. ]<br> | |||

7) [http://aem.asm.org/cgi/content/full/67/9/4137?maxtoshow=&HITS=10&hits=10&RESULTFORMAT=&titleabstract=Lactobacillus+delbrueckii&searchid=1&FIRSTINDEX=0&resourcetype=HWCITLick, S., Drescher, K., and Heller, K. “Survival of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus in the Terminal Ileum of Fistulated Gottingen Minipigs. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2001. Volume 67. p.4137-4143. ]<br> | |||

8) [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?artid=178052&blobtype=pdfGilbert, C., D. Atlan, B. Blanc, R. Portailer, J. E. Germond, L. Lapierre, and B. Mollet. 1996. “A new cell surface proteinase: sequencing and analysis of the prtB gene from Lactobacillus delbruekii subsp. bulgaricus”. Journal of Bacteriology. 1996. Volume 178. p.3059-3065. ]<br> | |||

9) [Partanen, L., Marttinen, N., Alatossava, T. “Fats and Fatty Acids as Growth Factors for Lactobacillus delbrueckii”. 2001. Volume 24. p.500-506. ]<br> | |||

10) [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?Db=genome&Cmd=ShowDetailView&TermToSearch=19473National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Genome. Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. 11842, complete genome. ]<br> | |||

11) [http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=16754859Van de Guchte, M., Penaud, S., Grimaldi, C., Barbe, V., Bryson, K., and others. “The complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus bulgaricus reveals extensive and ongoing reductive evolution”. PNAS. 2006. Volume 103. p.9274-9279]<br> | |||

12) [http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/links/doi/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00631.xMichaylova, M., Minkova, S., Kimura, K., Sasaki, T., and Isawa, K. “Isolation and characterization of Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus from plants in Bulgaria”. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2007. Volume 269. p. 160-169.] <br> | |||

13) [Easo, J.G., Measham, J.D., Munroe, J., and Green-johnson, J.M. “Immunostimulatory Actions of Lactobacilli: Mitogenic Induction of Antibody Production and Spleen Cell Proliferatioin by Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Lactobacillus acidophilus”. 2002. Volume 14. p.73-83.] <br> | |||

Edited by Maryruth Penetrante student of [mailto:ralarsen@ucsd.edu Rachel Larsen] | |||

Edited by | Edited by KLB | ||

Latest revision as of 14:28, 10 December 2010

A Microbial Biorealm page on the genus Lactobacillus delbrueckii

Numbered ticks are 11 µM apart.

Gram-stained.

Photograph by Bob Blaylock.

Classification

Higher order taxa

Bacteria (Domain); Firmicutes (Phylum); Bacilli (Class); Lactobacillales (Order); Lactobacillaceae (Family)[Others may be used. Use NCBI link to find]

Species

|

NCBI: Taxonomy |

Lactobacillus delbrueckii

subspecies: bulgaricus, lactis, delbrueckii, and indicus

Description and significance

Lactobacillus us delbrueckii is a rod shaped, gram positive, non-motile bacterium. Common to the species is its ability to ferment sugar substrates into lactic acid products under anaerobic conditions. As such, L. delbrueckii are generally found in dairy products such as yogurt, milk, and cheese with the exception of L. delbrueckii subsp. delbruecki which reside in vegetable sources (3). There are four subspecies differentiated by its metabolites and its internal genetics known to date. The most recent accepted subspecies, L. delbrueckii subsp. indicus was isolated from an Indian dairy (1). In contrast, Dr. Stamen Grigorov isolated L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus from a yogurt sample in 1905.

The properties that define L. delbrueckii as a homofermentive lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are not confined by its metabolic end product D-lactate and L-lactate. L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus has been proven to have probiotic affects on humans and animals which include improved lactose tolerance and its ability to stimulate immune responses (4, 5, 7). Past debates against this information questioned the ability of the latter to survive within low acidic environments and the gastric juices of the human gastrointestinal tract. A phosphopolysaccharide produced by L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus has the capability to enhance phagocytosis of macrophages in mice (4).

Genome structure

The circular genome of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bugaricus ATCC 11842 was completed in May of 2006. Composed of 1,864,998 nucleotides, it has an unusually high G-C content (49%) in comparison to other species of the genus Lactobacilli to which it belongs. Of the 2,217 genes present 1,562 code for proteins and 533 as pseudo genes (10). Genomic features such as these, as well as insertion sequence patterns are indicative of its adaptation in the dairy industry and support the theory of a rapid evolutionary phase (11).

Of the 1,562 genes that code for proteins prtB and the lac operon are important to the homofermentative properties of L. delbrueckii. Within the lac operon is the lacS, lacZ, and lacR genes that encodes for the uptake and breakdown of lactose.(3) The lacS gene codes for lactose permease responsible for the ability to transport lactose in through the membrane. The important enzyme B-galactosidase necessary for lactose metabolism is encoded in the lacZ gene. Downstream of lacZ is the regulatory gene lacR.

Cell structure and metabolism

As a gram positive bacterium L. delbrueckii retains its purple stain under the Gram test. Unique to microbes of this type is a thick cell wall and a cell membrane. The absence of an outer membrane which functions as an additional barrier could be a reason for its sensitivity to bacteriophage attacks (2).

Proteases encoded by the prtB gene are found anchored along the cell wall of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and lactis ; and most likely in the subsp. indicus. The ability of the subspecies’ to grow in dairy is owed to the enzymatic activity in casein breakdown to expose essential amino acids, in addition, to constitutive or inducible expression of the lacZ gene. (8,4)

Significant to the four L. delbrueckii subspecies are the number and types of substrates it can metabolize. As noted, such properties are restricted to enzyme expression within its genome. L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and subsp. indicus can metabolize lactose, glucose, fructose, and mannose. In addition to these, L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis catabolizes galactose, sucrose, maltose, trehalose and other modified carbohydrates.(4)

Ecology

As an inhabitant of fermented dairy products and producers of lactic acid Lactobacillus delbrueckii, with the exception of L. subsp. delbrueckii, is the cause of its low acidic environment. The nutritional requirements are adapted to the bacterium’s environment; as such includes but are not limited to amino acids, vitamins, carbohydrates and unsaturated fatty acids (9). L. delbrueckii has an optimal growth temperature of 40-44 °C under anaerobic conditions(3). Specifically, L. subsp. bulgaricus has a symbiotic relationship with Streptococcus thermophilus as it coexists in starter lactic acid bacteria cultures.

Pathology

Lactobacillus delbrueckii is non-pathogenic. In fact, it is widely used in the food industry and can be found in yogurts, milks, vegetables, and cheeses.

Application to Biotechnology

Of the four subspecies known to date L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and subsp. lactis are most important to the dairy industry, as starter cultures for the production of fermented milk, yogurt, and cheese. Economic losses would be significant if the fermentation process of the widely used Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and subsp. lactis were hindered. Thus, the dairy industry must be able to detect bacteriophages and adjust conditions of production to ensure high quality for safety and shelf life (2). Due to the symbiotic relationship of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus with Streptococcus thermophilus the latter has been examined simultaneously.

Current Research

Specific strains of Lactobacilli has been shown to have mitogenic effects and aid in spleen cell proliferation. Heat treated YS strains of L. delbrueckii subspecies bulgaricus and L. acidophilus directly induced generation of IgM and IgG by murine spenocytes and was dependent on bacterium concentrations in contrast to ATCC strains. The former was most effective at amounts of 5×106 and 2 × 107 Lactobacilli ml–1. Antibody concentrations were determined with ELISA and Fisher’s test. In addition, strains YS and ATCC of both Lactobacilli species induced lymphocyte proliferation. L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus was shown to activate polyclonal B-cells indicated from the maintenance of high antibody levels upon removal of Lactobacilli antibodies. (13)

A study suggested the practical use of multiplex PCR to detect bacteriophages at any stage of manufacture. The method proved to be simple and quick, all the while guaranteed the minimum quality requirements of the products. Although results indicated low amounts of L. delbrueckii phages in the samples used, a relatively higher amount was found of S. thermophilus phages. These results are consequent of the increasing proportion of S. thermophilus used in starter cultures. (2)

Lactobacillus delbrueckii, generally, can not be found outside starter cultures in the dairy industry. The natural environment from which it originated is not known for sure. A recent study reported the isolation and characterization of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus along with its symbiont Streptococcus thermophilus from plants in Bulgaria on the basis of tradional yogurt preparation. Six hundred sixty five plant samples, with the target plant Cornus mas were collected from four sites away from human habitation. Identification of the L. subsp. bulgaricus was determined via phenotype analysis, Pulse field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis, and PCR methods. The cultures samples that grew at 45°C were rod shaped, produced D-lactate, generated a DNA fragment of 1065 base pairs with the primers LB1/LLB1, and showed proteolytic activity. From the 665 plant samples L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and or S. thermophilus were isolated, a majority of which came from Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria. (12)

References

1) F., Felis, Giovanna E., Castioni, A., Torriani, S., and Germond, J. “Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. indicus subsp. nov., isolated from Indian dairy products”. 2005. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. Volume 55. p. 401-404.

2) [Del Rio, B., Binetti, A.G., Martın, M.C., Fernandez, M., Magadan, A.H., and Alvarez, M.A. “Multiplex PCR for the detection and identification of dairy

bacteriophages in milk”. Food Microbiology. 2007. Volume 24. p.75-81. ]

3) J., Lapierre, L., Delley, M., Mollet, B., Felis, G., and Dellaglio, F. “Evolution of the Bacterial Speies Lactobacillus delbrueckii: A Partial Genomic Study with Reflections on Prokaryotic Species Concept”. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2003. Volume 20. p. 93-104.

4) [Kitazawa, H., Yasuyuki, I., Uemura, J., Kawai, Y., Saito, T., Kaneko, T., Noda, K., and Itoh, T. “Augmentation of macrophage functions by an extracellular phophopolysaccharide from Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus”. Food Microbiology. 2000. Volume 17. p.109-118. ]

5) M., Callegari, M., Ferrari, S., Bessi, E., Cattibelli, D., Soldi, S., Morelli, L., Feuillerat, N., and Antoine, J. “Survival of Yogurt Bacteria in the Human Gut”. Applied Environmental Microbiology. 2006. Volume 72. p.5113-5117.

6) [Perea Velez, M., Hermans, K., Verhoeven, T.L.A., Lebeer, S.E., Vanderleyden, J., and De keersmaecker S.C.J. “Identification and characterization of starter lactic acid bacteria and probiotics from Columbian dairy products”. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2007. Volume 103. p. 666-674. ]

7) S., Drescher, K., and Heller, K. “Survival of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus in the Terminal Ileum of Fistulated Gottingen Minipigs. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2001. Volume 67. p.4137-4143.

8) C., D. Atlan, B. Blanc, R. Portailer, J. E. Germond, L. Lapierre, and B. Mollet. 1996. “A new cell surface proteinase: sequencing and analysis of the prtB gene from Lactobacillus delbruekii subsp. bulgaricus”. Journal of Bacteriology. 1996. Volume 178. p.3059-3065.

9) [Partanen, L., Marttinen, N., Alatossava, T. “Fats and Fatty Acids as Growth Factors for Lactobacillus delbrueckii”. 2001. Volume 24. p.500-506. ]

10) Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Genome. Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. 11842, complete genome.

11) de Guchte, M., Penaud, S., Grimaldi, C., Barbe, V., Bryson, K., and others. “The complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus bulgaricus reveals extensive and ongoing reductive evolution”. PNAS. 2006. Volume 103. p.9274-9279

12) M., Minkova, S., Kimura, K., Sasaki, T., and Isawa, K. “Isolation and characterization of Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus from plants in Bulgaria”. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2007. Volume 269. p. 160-169.

13) [Easo, J.G., Measham, J.D., Munroe, J., and Green-johnson, J.M. “Immunostimulatory Actions of Lactobacilli: Mitogenic Induction of Antibody Production and Spleen Cell Proliferatioin by Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Lactobacillus acidophilus”. 2002. Volume 14. p.73-83.]

Edited by Maryruth Penetrante student of Rachel Larsen

Edited by KLB